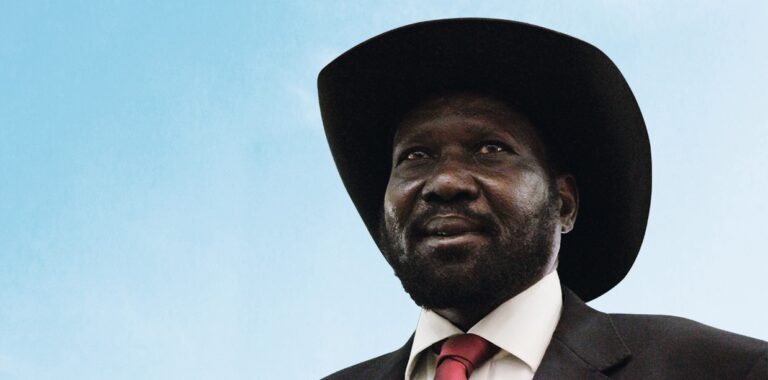

When presidential decrees become the central tool of governance, the state itself begins to erode. For more than a decade, President Salva Kiir Mayardit has relied on sudden, unexplained decrees to hire, fire, reshuffle, promote, demote, and reorganise nearly every corner of the government. While decrees are constitutionally permitted under specific circumstances, their sheer frequency and unpredictability have turned South Sudan’s public administration into a fragile, unstable machine.

The first casualty has been institutional stability. No minister, undersecretary, or commissioner can effectively plan long-term when he or she may be removed at any moment. Development programs stall, annual budgets lose coherence, and ministries operate in reaction mode rather than strategic mode. A government cannot function when its leaders are always waiting for the next decree instead of building systems that outlast individual officeholders.

Second, this decree culture has destroyed performance-based leadership. In a healthy democracy, officials are assessed by clear indicators—service delivery, accountability, and results. In South Sudan, however, job security depends not on performance but on proximity to power. Loyalty is rewarded; competence is optional. This creates a public service where fear replaces innovation, and silence is safer than independent thinking.

The third impact is the politicisation of appointments. Decrees have become the currency of political survival, turning public offices into ethnic bargaining chips. This has entrenched tribal patronage networks at every level of government. As a result, professionalism suffers, and citizens come to see government institutions as belonging to groups rather than to the nation.

Economically, the consequences are equally damaging. Sudden changes in key ministries such as Finance, Petroleum, and Investment disrupt revenue collection, scare away investors, and undermine donor confidence. No partner—whether diplomatic or commercial—can plan effectively when they cannot predict who will be in office tomorrow. South Sudan’s development cycle is constantly reset because new officeholders take months to understand their roles, only to be removed shortly after.

Perhaps the most troubling effect is the erosion of constitutional order. Parliament and the judiciary are sidelined when critical decisions are made through decrees rather than through transparent legislative or institutional processes. Executive overreach becomes normalised, weakening separation of powers and turning the government into a one-man centre of authority.

Finally, this culture breeds deep public distrust. Citizens have grown tired of appointments made at midnight, dismissals without explanation, and governance that feels improvisational. A population that no longer trusts its institutions becomes disengaged, hopeless, and less willing to participate in nation-building.

South Sudan’s future depends not on the frequency of presidential decrees but on the strength of its institutions. What the country urgently needs is stability, predictability, and continuity—three pillars that decree-driven governance has systematically dismantled.

If South Sudan is to break out of political stagnation and chart a path toward meaningful development, President Kiir must move away from ruling by decree and empower institutions to govern effectively. A nation cannot mature when its government resets itself every few weeks. The time has come to rebuild a governance culture rooted in accountability, not unpredictability.

The writer, John Bith Aliap, is a South Sudanese political analyst and commentator on governance, leadership, and state-building in post-conflict societies. He can be reached via email: johnaliap2021@hotmail.com

The views expressed in ‘opinion’ articles published by Radio Tamazuj are solely those of the writer. The veracity of any claims made is the responsibility of the author, not Radio Tamazuj.