The recent border tensions between South Sudan and Uganda have raised significant concern, particularly regarding the manner in which they were addressed. The South Sudanese delegation was composed exclusively of military officials. While the national army is tasked with protecting territorial borders, the negotiation of international boundaries requires a multidisciplinary approach. Such a task necessitates the expertise of lawyers, lawmakers, historians, local leaders, and, to some extent, civil society organizations. The exclusion of these critical actors significantly undermines the legitimacy and effectiveness of the process.

A further limitation lies in the composition of the South Sudanese delegation. The seven high-ranking military officers who represented South Sudan were not equivalent in profile to their Ugandan counterparts. Although they held comparatively higher military ranks, they possessed lower levels of formal education, leaving them at a disadvantage in negotiations. In contrast, Uganda deployed officials who, though of lower military rank, had greater technical capacity. This imbalance provided Uganda with a dual advantage: first, by underestimating South Sudan through the deployment of lower-ranking officials, and second, by exploiting the limited expertise of the South Sudanese representatives. A case in point occurred in Eastern Equatoria, where a junior South Sudanese officer, when questioned, affirmed that the disputed land belonged to South Sudan, citing the state concerned, yet he was still subjected to intimidation.

Uganda’s claim that the construction of a road constituted evidence of territorial ownership represents another point of contention. This argument is legally unfounded. According to international law, sovereignty over borders is not determined by acts of development but by legally recognized agreements and historical demarcations. The principle of uti possidetis juris, recognized in the Charter of the Organization of African Unity (OAU, 1964) and reaffirmed by the African Union (AU), stipulates that post-colonial states shall respect the boundaries inherited at independence. This principle, consistently upheld by the International Court of Justice (ICJ), reinforces the illegitimacy of claims based on unilateral acts such as road construction. Encroachment through infrastructure projects can therefore be considered a violation of the territorial integrity of South Sudan under both Article 2(4) of the UN Charter and the AU Constitutive Act (2000), which prohibits aggression and annexation of another member state’s territory.

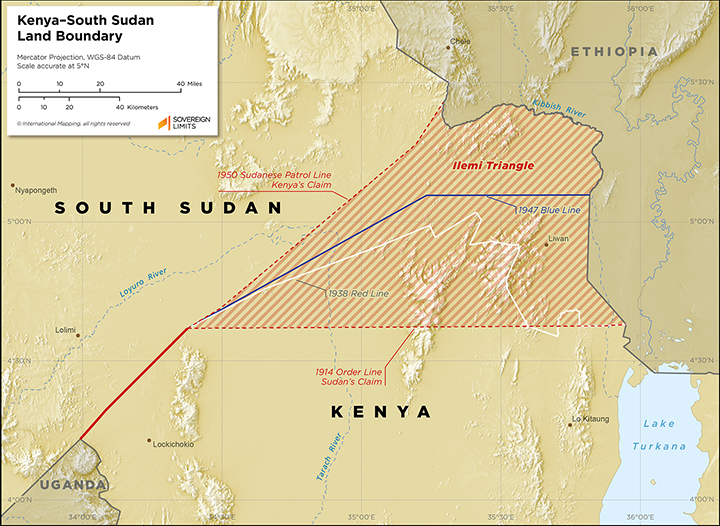

Despite this, one South Sudanese commander indicated that a new boundary demarcation would be undertaken between the two countries. Such a proposal is problematic, as the boundary between South Sudan and Uganda was already demarcated in 1956, before Sudan’s independence. Any re-demarcation risks legitimizing Uganda’s encroachment and may amount to the surrender of South Sudanese territory. What is required instead is verification of encroachment through joint boundary commissions, supported by colonial-era maps and archival evidence, in line with AU and UN dispute resolution frameworks.

Equally troubling is the fact that the South Sudanese delegation reportedly signed a document, the content of which remains unknown to both parliamentarians and the wider citizenry. International legal practice requires that treaties and agreements between sovereign states reflect the interests of the people and comply with principles of transparency and accountability. The Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties (1969) stipulates that treaties must be concluded with the free and informed consent of states, and that agreements signed without proper authority or in secrecy may be considered invalid. The lack of public disclosure raises the possibility that the agreement involved concessions of land to Uganda, thereby undermining South Sudanese sovereignty. This concern is further reinforced by statements from the Chief of Defence Forces (CDF), who blamed South Sudanese citizens for resisting Ugandan encroachment, despite their legitimate role in defending their territory.

In conclusion, it is notable that during the regime of President Omar al-Bashir in Sudan, there were no major border confrontations between Uganda and Southern Sudan. By contrast, under President Kiir’s administration, there have been more than ten such incidents. This trend highlights not only weaknesses in governance but also the absence of a coherent national strategy for border protection. More critically, it exposes the contradictions between President Kiir’s claim of being a liberator of South Sudanese land and his administration’s apparent failure to safeguard territorial integrity. From the perspective of international law, South Sudan must assert its rights within the framework of uti possidetis juris, the UN Charter, and the AU Constitutive Act, while ensuring that future negotiations include legal experts, historians, and civil society representatives. Without such measures, South Sudan risks the gradual erosion of its sovereignty through piecemeal concessions.

The writer is a social researcher, activist, and critic. He can be reached via mathewonenboss@gmail.com.

The views expressed in ‘opinion’ articles published by Radio Tamazuj are solely those of the writer. The veracity of any claims made is the responsibility of the author, not Radio Tamazuj.