A neighborhood is a geographic area or community where people live, interact, and share a sense of belonging. According to various sources, a neighborhood can be defined as: “A localized community within a larger city, town, suburb, or rural area where people live, interact, and share a sense of belonging.” (Source: Encyclopedia). “Neighborhoods are social and geographic units, which provide a sense of community and identity to residents.” (Source: Urban Studies Research). A neighborhood is characterized by physical proximity, with residents living close to one another. Neighborhoods often involve social interaction among residents, fostering a sense of community and belonging. Neighborhoods have a shared identity, shaped by factors such as blood ties, culture, history, or socioeconomic status.

Neighborhoods play a crucial role in fostering social cohesion and community development. Neighborhoods significantly impact residents’ quality of life, influencing factors such as safety, health, and well-being. Neighborhoods provide a sense of belonging and identity for residents, shaping their experiences and perceptions. The ideals of a good neighbour are rooted in various perspectives, including historical, biblical, and contextual views. Jesus taught that loving your neighbour as yourself is the second greatest commandment (Matthew 22:39). This involves showing compassion, empathy, and kindness to those around us, regardless of their circumstances. The parable of the Good Samaritan (Luke 10:25-37) exemplifies selfless love and care for others, demonstrating that being a good neighbour means going beyond mere proximity and actively engaging in acts of kindness and support. Biblical teachings encourage forgiveness, humility, and willingness to listen and learn from others (Ephesians 4:25; Romans 15:2).

In ancient societies, being a good neighbour was crucial for survival and well-being. This involved mutual support, cooperation, and a sense of community. Historical teachings emphasize the importance of treating others with respect, fairness, and kindness, regardless of their social status or background. Being a good neighbour involves understanding and empathizing with others, recognizing that everyone has their struggles and challenges. Good neighbours offer practical support and assistance, whether it is helping with daily tasks or providing emotional support during difficult times. Good neighbours respect and appreciate differences in culture, opinion, and lifestyle, recognizing that these differences enrich our communities.

“Love your neighbour as yourself” (Leviticus 19:18; Matthew 22:39).

“Go and do likewise” (Luke 10:37).

“Love does no harm to a neighbour; therefore love is the fulfilment of the law” (Romans 13:10).

“The entire law is fulfilled in a single decree: ‘Love your neighbour as yourself’” (Galatians 5:14).

“Worship Allah and associate nothing with Him, and to parents do good, and to relatives, orphans, the needy, the near neighbour, the neighbour farther away, the companion at your side, the traveller, and those whom your right hands possess.” (Quran 4:36).

The Quran encourages Muslims to be mindful of their neighbours’ feelings and well-being, ensuring they do not cause harm or discomfort to those around them.

Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him) stressed the importance of being kind to neighbours, regardless of their background or faith.

He said, “The best of companions to Allah is the one who is the best to his companions, and the best of neighbours to Allah is the one who is the best to his neighbours” (Tirmidhi).

The Prophet also emphasized the need to help neighbours in times of difficulty, saying, “A man is not a believer who fills his stomach while his neighbour is hungry” (Authenticated by Al-Albani).

In Islam, treating neighbours well is considered an essential aspect of one’s faith and character. The Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him) said, “He will not enter Paradise whose neighbour is not secure from his wrongful conduct” (Muslim). A good neighbourhood is seen as a means of building strong, harmonious communities, where individuals look out for one another’s well-being.

South Sudan and Uganda’s Equatoria, West Nile, and Northern Regions have blood, cultural, and historical ties beyond political, administrative, and artificial boundaries.

The historical ties among Equatoria, West Nile, and Northern Regions of South Sudan and Uganda are deeply rooted in pre-colonial, colonial, and post-colonial history. Equatoria, a region in southern South Sudan, was originally a province of Anglo-Egyptian Sudan, and it contained most of the northern parts of present-day Uganda, including Lake Albert and the West Nile region. These areas, now considered Uganda, were parts of Equatoria under Anglo-Egyptian rule. In 1870, British explorer Sir Samuel Baker established Equatoria as an Egyptian province to control interests over the Nile River. The region played a significant role in the struggle for autonomy in Southern Sudan, with Equatorians being instrumental in the fight against Arab domination in the Sudan.

The Nile River is a lifeline of relationships in Africa. When I met an Egyptian in Sweden in November 2024. He called me “brother”. He explained that “we drink from the same source of water, the Nile River”. We exchanged laughter and jokes. Indeed, the Nile River passes through Kajo-Keji to Egypt.

The Anya Nya movement, led by Equatorian leaders such as Rev. Fr. Saturnino Ohure, emerged as a separatist force demanding a separate, independent Southern Sudanese nation. He was one of the pioneers of the Southern Sudan Federal Party and the leader of the Equatoria Corps manning the Torit Mutiny alongside Major General Emidio Tafeng, Ali Gbatala, Daniel Jumi Tongun, Marko Rume, General Joseph Lagu Yanga, Aggrey Jaden, and Reynaldo Loleya, among others. This movement marked the beginning of the first civil war in Southern Sudan. Unfortunately, history had it that Rev. Fr. Ohure’s murder was ostracized in Uganda by a Ugandan. He was killed by a Ugandan soldier near Kitgum on January 22, 1967. This somehow derailed the Southern Sudan independence struggle, which started on August 18, 1955. This August 18, 2025, South Sudan actually marks 70 years of insurgency in the quest for freedom and political stability.

70 years down the road, the spirit for justice, liberty, and prosperity still reigns. Oh, Dear God, where can this nation get justice, liberty, and prosperity?

The 1972 Addis Ababa Agreement granted autonomy to the South, with Equatoria being one of the three provinces. This agreement resulted in a hiatus in the Sudanese civil war from 1972 to 1983. The agreement, which later turned into a fiasco, was conditioned by Uganda’s Dr Milton Obote and Field Marshal Idi Amin Dada turning back against General Joseph Lagu’s Anya Nya movement to the Arab Khartoum-dominated regime. Such a move derailed the Southern Sudanese quest for freedom from the Arabic yoke. However, the struggle went on with persistence and determination for justice, liberty, and prosperity to date.

The 1983 Sudan People’s Liberation Army /Movement (SPLA/M) led by Dr John Garang De Mabior, however, got support from Uganda’s National Resistance Movement (NRM) led by General Yoweri Kaguta Museveni.

Ironically, Dr Garang met his death in a Ugandan military aircraft together with some Ugandan nationals. What was generally perceived as an accident with some degree of doubt has derailed the Southern Sudanese quest for freedom, peace, prosperity, justice, and stability. There were clouds of doubts, and indeed, now the clouds of doubts and despair are still hovering over the skies of South Sudan.

As Uganda’s government under President Museveni was backing the SPLA/M, the Sudanese government under Field Marshal Omar Hassan El Bashir was supporting Uganda’s Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) from Gulu District and West Nile Bank Front under Juma Oris and Uganda National Liberation Front II under late Major General Ali Bamuze from Yumbe District.

In mid-December 2013 eruption of violence in Juba, South Sudan, Uganda’s UPDF intervened by taking the side with forces loyal to President Salva Kiir Mayardit against his former Vice President, Dr Riek Machar Teny. The intervention, which was seen as both positive and negative at the same time, had both positive and negative impacts on South Sudan’s political landscape.

The UPDF was later withdrawn to effect the 2015 peace accord, which unfortunately was broken in July 2016. This intensified political and humanitarian crises, leading to losses of at least 400,000 lives and the displacement of millions of people from South Sudan. Let alone economic and social losses.

Uganda and other neighbouring countries played key roles in the recovery of the 2015 peace deal, which was later signed on September 22, 2018. The 2018 revitalized agreement saw some nationwide calm and hope for political stability for nearly five years until the recent incident in Nasir County, Upper Nile State, which consequently led to the house arrest of the First Vice President, Dr Riek Machar Teny, and abrogation of the 2018 peace accord in totality.

In March 2025, before the house arrest of Dr Machar, the UPDF was deployed in Juba and Upper Nile State to further complicate the country’s troubles.

Violence is threatening to grip the country again.

Yet, Uganda as a government was one of the guarantors of the 2018 peace accord. Is the Ugandan government interested in South Sudan’s peace settlement?

Is the Ugandan government enjoying the host of thousands of refugees from South Sudan and beyond?

Is Uganda, as a government, living up to its Godly motto, ‘For God and my country’?

Is it Godly to fan the flames of a neighbour’s home?

Amidst all such complications and complexities between Uganda and South Sudan, either side has always been receiving and hosting refugees or self-settlers, who could integrate into a sanctuary community on either side, depending on cross-border relations.

The 1956 border delineation between the Sudan and Uganda was rooted in a colonial history. The boundary was initially delimited by a 1914 British Order, which described the border as following the historic tribal boundaries of the indigenous communities. Specifically, the boundary between the Nile and Kaya rivers was based on tribal territories, with a 1936 agreement outlining the alignment.

The border originated from the colonial administrative line separating the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan from the Uganda Protectorate.

The boundary was drawn based on tribal territories, with local chiefs and district officials playing a significant role in shaping the border.

The border has been a source of tension and disputes between the Sudan and Uganda, with issues of taxation, jurisdiction, and resource control contributing to the conflicts.

Attempts to demarcate the border have been ongoing, with a recent agreement between Uganda and South Sudan to establish a joint technical committee for delimitation.

The border stretches for approximately 500 kilometres from the tripoint with Kenya in the east to the tripoint with the Democratic Republic of the Congo in the west. There are areas of contention, particularly near the South Sudanese town of Kajo-Keji and Pajok, where explicit opposing claim lines exist.

Why should there be border demarcation in Africa when the continent is striving for Pan-Africanism with the quest for the United States of Africa?

The question of border demarcation in Africa, particularly in the context of Pan-Africanism, is complex and multifaceted.

Many African borders were arbitrarily drawn by colonial powers, often dividing ethnic groups and communities. Demarcating borders helps clarify boundaries and reduce conflicts. Clearly defined borders are essential for maintaining state sovereignty and territorial integrity, which are fundamental principles of international law. While Pan-Africanism promotes economic integration and cooperation, clearly defined borders facilitate trade and economic activities by reducing uncertainty and disputes. Well-defined borders help prevent conflicts and ensure regional stability, creating a more conducive environment for economic development and cooperation. Some argue that borders should be more fluid to allow for the free movement of people and the preservation of cultural and ethnic ties across borders.

In the context of Pan-Africanism, border demarcation can be seen as a means to achieve greater regional integration and cooperation. Clearly defined borders facilitate regional cooperation and integration initiatives, such as the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA). By reducing border disputes and uncertainty, countries focus on economic development and cooperation, ultimately benefiting from increased trade and investment. Well-defined borders help build trust and cooperation among nations, contributing to a stronger sense of community and shared identity.

The concept of global citizenship, based on the idea that everyone belongs to a global community and shares a common humanity, transcending national borders, is an initiative to embrace rather than the so-called nationalism or Pan-Africanism, which have limits. Global citizenship emphasizes our shared humanity and the interconnectedness of the world, promoting a sense of responsibility towards one another. Many challenges, such as climate change, pandemics, and economic inequality, require global cooperation and collective action. Global citizenship advocates for the universal application of human rights, regardless of nationality or borders. Global citizenship encourages cultural exchange, understanding, and appreciation, promoting peace and cooperation.

Regarding border conflicts in Africa and beyond, global citizenship can be seen as a way to foster cooperation by emphasizing our shared humanity and global interconnectedness. Global citizenship encourages cooperation and diplomacy to resolve border conflicts. Global citizenship helps promote cross-cultural understanding and empathy, reducing tensions and conflicts between nations. By focusing on global challenges and shared humanity, global citizenship helps address the root causes of border conflicts, such as economic inequality, resource competition, and historical grievances.

What perhaps limits global citizenship is the argument that it might erode national sovereignty and the importance of national borders. Border conflicts often have deep cultural and historical roots, requiring context-specific solutions, which may not be fully addressed by global citizenship alone.

Implementing global citizenship would require significant changes to international relations, global governance, and individual identities. Yet, with or without border delineation, the people of South Sudan’s Equatoria and Uganda’s Northern Region share blood, cultural, and historical ties, with many Equatorians fleeing to Uganda, Kenya, and other neighbouring countries during times of conflict and the reverse was, is and will be true for Ugandans, Kenyans, Congolese and others.

The Sudanic Ethnic Groups in Uganda and South Sudan include Luo-speaking groups. The Luo people have blood, historical, and cultural ties to both Uganda and South Sudan. In Uganda, they are found in the northern region, particularly in Acholi land, while in South Sudan, they are found in the eastern part of the country, particularly in Magwi County of Eastern Equatoria State. The Nilotic groups in South Sudan. The Nilotic people, including the Dinka, Nuer, and Shilluk, are prominent in South Sudan. Some Nilotic groups, such as the Acholi and Alur, are also found in Uganda. The Central Sudanic groups, including the Lugbara, Aringa, and Ma’di, are found in Uganda’s West Nile region and have blood, cultural, and linguistic ties to groups in South Sudan. Many of these groups have been displaced or divided by colonial borders, leading to cultural and linguistic differences.

Lugbara people are part of the Central Sudanic language family, primarily residing in the West Nile region of Uganda, with some populations in the Democratic Republic of Congo and a small number in South Sudan. They speak the Lugbara language, which is similar to the Ma’di language, and share cultural similarities with the Ma’di people. The Lugbara are related to other Central Sudanic peoples in Equatoria, including the Avukaya, Muru, Logo, Aringa, Keliko, Omi, Olu’bo, and Ma’di. The Acholi and Ma’di have blood, cultural, and linguistic ties with groups in South Sudan’s Equatoria Region. The region has experienced migration and conflict, leading to complex relationships between groups across the borders. Some tribes, like the Kakwa, Kuku, and Ma’di, are divided between South Sudan and Uganda, contributing to the complexity and advantage of the relationship.

The Kuku, Ma’di, Aringa, and Acholi are ethnic groups residing in both Uganda and South Sudan, sharing blood, cultural, and linguistic ties. The Kuku people are part of the Bari-speaking group in South Sudan, primarily residing in Kajo-Keji County, Central Equatoria State. Others had entered deeper into Uganda since 1922. Uganda and South Sudan are home to all tribes from either side. The Kuku have blood, historical, and cultural connections with other Bari-speaking groups, including the Bari, Pojulu, Kakwa, Nyangwara, and Mundari. They have related groups of people in Eastern Equatoria as well as Ethiopia. The Ma’di people are a Central Sudanic ethnic group found in Uganda’s West Nile region and neighbouring areas in South Sudan. They have blood, linguistic, and cultural similarities with the Lugbara and other Central Sudanic groups. The Aringa people are also a Central Sudanic ethnic group, closely related to the Lugbara and Ma’di. The relationship among Ma’di, Aringa, and Kuku is centred on a shared geographic proximity, tradition, customs, faith, and cultural exchange with other groups in the region. They share similar clans such as Moli, Moipi, Romogi, Kulyenuk, Lipi, and Gimero, among others.

All in all, the border communities have blood ties and therefore, antagonising them is evil, ill-advised, and wicked of the two oligarchies manning Uganda and South Sudan affairs. It is a practical homicide.

The Bible warns against individuals who stir up conflict and division within communities. Proverbs 6:16-19 lists “a person who stirs up conflict in the community” as one of the six things God hates. Proverbs 13:10 states, “Pride leads to conflict; those who take advice are wise.” Those who prioritize their interests and pride often spark discord. Proverbs 28:25 notes, “One who is greedy stirs up strife; but one who trusts in the Lord will prosper.”

Those who cause division will be held accountable for their actions. Surah An-Naml (27:78) reassures that Allah will judge the differences among various sects with His perfect knowledge and might. Those who cause division and discord will face judgment from Allah. Surah Al-An’am (6:159) says, “As for those who divide their religion and break up into sects, you have no part in them in the least. Their affair is with Allah; He will in the end tell them the truth of all that they did”. The Quran condemns sectarianism and encourages believers to avoid disputes and arguments. Al-Anfal (8:1) advises believers to “reconcile your mutual differences”.

Historically, the border communities fought as brothers and sisters, but reconciled quickly after learning from the bitter part of violence and realizing the dividends of peace. The Kuku believe in customary land regimes, where land is regulated by community norms and traditions. They had a system of land rights, which granted owners the right to build, cultivate, graze, and dig wells on their land. The Kuku have traditionally lived near the border of South Sudan and Uganda with unmeasured resilience and resistance, with their territory extending into the Moyo and Yumbe districts. Their borders are often porous, allowing for negotiation and contact between communities. The Kuku believe that their ancestors play a significant role in their daily lives, and they maintain a strong family tree to keep them close to God (Ŋun). They believe that God speaks and acts to people through their ancestors. The Kuku have a strong spiritual system, believing in one God who lives above the skies and communicates with people through ancestors. They also believe in good and bad spirits called Mulȍkȍ.

The Kuku have a system of customary laws, which govern their community, including rules related to land use, crime, and punishment. For example, if someone commits a crime, they may be required to pay a certain number of animals to the offended family or tribe for cleansing or compensation for appeasement. The Kuku have a decentralized administrative system, with decision-making power resting with elders and community leaders. Chiefs are associated with water and are responsible for rain control during crop-growing seasons. In Kuku society, elders are highly respected, followed by male adults, adult women, and children. This social hierarchy reflects their cultural values and traditions. The Kuku are primarily farmers, relying on mixed farming and crop rotation. They grow crops like sorghum, cassava, maize, pigeon peas, and millet, among others. They also engage in animal rearing, beekeeping, and hunting. The Kuku treat land and soil as sacred. They do not encourage any quarrel over land as they believe that the soil can turn to consume any land grabber for generations over generations until the land becomes desolate. The Kuku traditional customs do not appreciate artificial land or border demarcation.

The majority of Aringa people adhere to Islam, with a small number following Christianity. Their spiritual practices are deeply rooted in their cultural heritage. The Aringa people have a rich cultural history, with traditional practices, which include hunting, cultivation, and small-scale livestock rearing. Many have also pursued business ventures and reside in urban areas while maintaining large households in rural villages. They have a complex history, including experiences as refugees in Sudan during the 1970s and 1980s. Many returned to Uganda and have since worked to rebuild their communities. The Aringa traditions and customs in relation to land are rooted in their cultural heritage and customary land tenure system, which is similar to other communities in Uganda. Land is owned and disposed of under customary regulations, with individuals, families, or communities holding rights to use and occupy the land. Family heads or clan leaders control land utilization, ensuring every family member has a right to use a portion of the land.

Land is often inherited within the family. Some land is communally owned, with shared rights for grazing, water sources, firewood collection, and other purposes. For land transactions, consent is required from community members, spouses, and children, depending on the land ownership structure. Many indigenous communities view land as a sacred living being with visible and invisible attributes and forces. This perspective emphasizes the importance of maintaining soil health for successful fertilization and the continuation of life. There is often a strong spiritual connection between communities and their land, with beliefs that land needs to be fed, nourished, and cured to maintain its health and productivity.

Ethnic Groups in Uganda include Bantu-speaking groups; Baganda (16.9% of the population; they practise patrilineal descent and speak Luganda), Banyankole, 9.5%. They have a high-ranking caste of pastoralists (Bahima) and a lower-ranking caste of farmers (Bairu); Basoga, 8.4%. Their traditional language is Soga, and the land is owned by clans and managed by the head of the clan. Bakiga, 6.9%. They have a history of conflict with the Banyoro over land and political positions. Luo-speaking groups include: Acholi, who are found in Northern Uganda and have historical and cultural connections with South Sudan’s Equatoria Region. Langi speak Luo and have cultural ties with the Acholi. Alur are settled in the West Nile region.

Atekerin (Nilo-Hamites) include: Karamojong. They are found in North-eastern Uganda and have cultural ties with neighbouring groups in South Sudan and Kenya. Iteso have a unique cultural identity and are found in Eastern Uganda. The Iteso share some linguistic and cultural similarities with the Kuku in South Sudan.

All these ethnicities and tribes are related across the two countries, South Sudan and Uganda, through intermarriages, ushering in uncles, aunts, in-laws, nephews, nieces, grandsons, and granddaughters.

Reconciling the ethnicities and the land could help promote cultural preservation and unity among the Sudanic people. These ethnicities were once in the Ladu Enclave. The Ladu Enclave was situated near the border of Uganda and South Sudan, with its exact location likely in the vicinity of the Imatong Mountains, which mark the edge of the Ugandan plateau to the north.

The region’s terrain is characterized by plateaus with gentle slopes and relatively flat areas, with an average elevation of about 1,100 metres above sea level. The Imatong Mountains and other ranges form a rim around the plateau, creating a rugged landscape and valleys. Deep and narrow valleys are present in the region, particularly in the Kigezi sub-region. The region is home to several lakes and rivers, including Lake Albert, located in the Western Rift Valley, forming part of Uganda’s border with the Democratic Republic of Congo.

The River Nile flows through Uganda, originating from Lake Victoria and eventually draining into the Mediterranean Sea, and other rivers include the Victoria Nile, Achwa, Okok, Pager, Kafu, Mpongo, and Katonga. The climate in the region is generally tropical, with two dry spells: December to February and June to August, as well as reliable rainfall throughout the year, with some areas receiving more rainfall than others. South Sudan and Uganda have strong economic ties, with trade and investment flowing between the two countries. The construction of roads and infrastructure has facilitated border trade and economic cooperation.

However, something is bedevilling the relationship between the two countries. The regimes of oligarchic warlords have created border disputes for their selfish political survival motives. The border between Uganda and South Sudan has been a source of tension, with recurrent disputes over resources and territory.

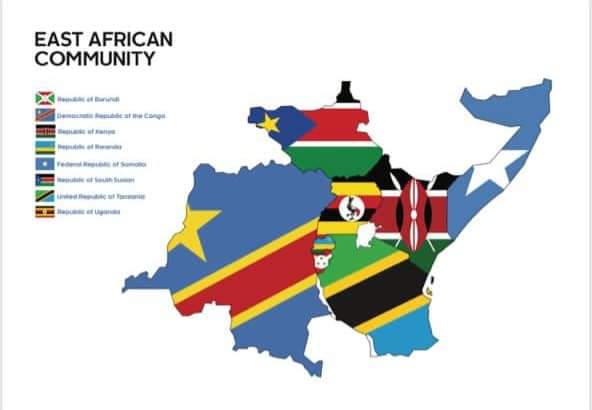

The East African Community (EAC) provides a framework for regional cooperation, promoting economic integration and cooperation between Uganda and South Sudan.

The East African Community (EAC) emphasizes the importance of a good neighbourhood, fostering social cohesion, and cultural exchanges to enhance the sense of identity and belonging among East Africans. A good neighbour in the EAC context is someone who respects and supports their community. Good neighbours engage in reciprocal relationships, sharing resources, offering assistance, and providing emotional support to one another. Community leaders and elders play a crucial role in mediating conflicts, resolving disputes, and promoting reconciliation among community members. Good neighbours prioritize the well-being of their communities by creating a harmonious and cohesive social structure.

On the other hand, a bad neighbour in the EAC context might be someone who disregards community values by failing to respect and support community members, or engaging in behaviours that harm others. One who creates conflict by refusing to resolve disputes or mediate conflicts, leading to divisions within the communities, and the one who disregards environmental sustainability by ignoring the importance of environmental protection and sustainable management of natural resources! Land and border encroachment in the East African Community (EAC) harms neighbourhoods in several ways, including forced evictions leading to the displacement of communities, resulting in loss of livelihood, cultural heritage, and social networks.

In Tanzania, the eviction of Masai community members from 1,500 square kilometres of land in Loliondo has sparked conversations on customary land tenure security. Communities are often pushed off their land without consent, leading to conflicts and social unrest. In Kenya’s Mau Forest, the Ogiek people have faced forced evictions, highlighting the need for recognition and protection of indigenous land rights.

Land grabbing and encroachment lead to conflicts between communities, governments, and investors. In the Democratic Republic of Congo, the Lonshi community has expressed concerns about the illegal occupation of their land by Tonga workers recruited by the mining company Sabwe Mining. The failure to recognize and secure local people’s property rights creates conflicts and social unrest, ultimately affecting regional stability. Land encroachment undermines local economies and exacerbates poverty.

In East Africa, land grabbing has contributed to the inequitable distribution of income, with powerful individuals and institutions grabbing land from vulnerable communities. The loss of land and natural resources also erodes cultural identity and community cohesion, leading to social and economic instability.

Recognizing and securing local people’s property rights is crucial for preventing conflicts and promoting social stability. The EAC needs to prioritize community-led land governance and ensure that land rights are respected and protected. Laws and policies, which recognize customary land tenure and promote community participation in decision-making, are essential for addressing the root causes of land-related conflicts.

The EAC has launched several initiatives aimed at promoting a good neighbourhood, including showcasing cultural exchange and regional identity; investing in education and skills development to empower citizens; promoting sustainable agriculture practices to ensure food security and poverty reduction; and prioritizing environmental protection and sustainable management of natural resources. But, are these practically working in the Uganda-South Sudan neighbourhood?

A good neighborhood in the EAC context leads to increased social cohesion by fostering a sense of community and belonging among East Africans; economic growth by promoting trade, investment, and economic development as well; and improved quality of life by enhancing the overall well-being of citizens through mutual support and cooperation.

Nevertheless, with ongoing recurrent border conflicts between South Sudan and Uganda, the concept of neighbourhood from government to government has become questionable and incomprehensible. Addressing the South Sudan-Uganda border dispute requires a multifaceted approach that incorporates Biblical, Quranic, and political perspectives.

The Bible emphasizes the importance of dialogue, forgiveness, and reconciliation in resolving conflicts. In Matthew 18:15, Jesus teaches us to address conflicts directly and respectfully by seeking a peaceful resolution. Similarly, Romans 12:18 encourages us to live at peace with everyone. The Bible also teaches us to respect human life, created in the image of God (Genesis 1:27). This respect should guide our actions and decisions, promoting peaceful coexistence and minimizing harm to civilians. The Bible emphasizes that God owns all land and territories, and humans are merely stewards (Psalm 24:1; Leviticus 25:23). The Bible highlights the importance of boundaries for maintaining order, protection, and identity (Deuteronomy 19:14; Proverbs 22:28).

Territorial boundaries can be contested spiritually, thus requiring prayer, fasting, and spiritual warfare to maintain and expand influence (Ephesians 6:12; Daniel 10:12-13). Proverbs 22:28 warns against moving ancient boundary stones, which were used to mark property lines. This act was considered a serious offense, equivalent to theft, and could lead to divine retribution. The Quranic perspective emphasizes that promises of land and territory are conditional upon obedience and fulfillment of God’s commands. Both the Bible and the Quran emphasize God’s sovereignty over territories and borders.

South Sudan and Uganda should prioritize diplomatic efforts to resolve the border dispute peacefully. This can involve negotiations, mediation, and cooperation with regional organizations like the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD) and the African Union (AU). A clear and agreed-upon border demarcation is essential to prevent future conflicts. This process should involve technical experts, community consultations, and mutual agreement. Reducing military presence and troop concentrations near the border helps decrease tensions and prevent accidental clashes. Providing humanitarian aid to affected communities helps alleviate suffering and promote stability. Strengthening regional cooperation and economic ties fosters a sense of mutual interest and cooperation, promoting the peaceful resolution of the border dispute.

The joint committee established to oversee the border demarcation process should resolve disputes and promote cooperation. Local communities should be engaged in the dialogue process, as they have intimate knowledge of the land and its history. International mediation provides a neutral platform for negotiations to resolve disputes peacefully. Prioritizing peaceful settlement over violence is crucial for long-term stability and regional integration.

Overall, as individuals and nations, we should monitor, evaluate, learn, and adjust on relationships with our neighbourhood to live meaningfully.

The writer, Yanta Daniel Elisha, is a Visiting Lecturer/Tutor of English, Communication & Research Methods at Kajo-Keji Christian College of The Episcopal University.

The views expressed in ‘opinion’ articles published by Radio Tamazuj are solely those of the writer. The veracity of any claims made is the responsibility of the author, not Radio Tamazuj.