In the corners of Mangateen IDP Camp, where dreams often disappear, wiped by the hot sun of Juba and sometimes floods, a young woman once sold groundnuts, water, and snacks, not for profit, but survival. The story of determination from Nyakang Madier, echoed without pity, but with purpose.

Before she became the face of youth-talk resilience, Nyakang was just “that hawker girl,” weaving through traffic and dodging boda-bodas (motorcycles). At only 12, she already looked after her siblings, betrayed by conflict situation, not in Juba, or a village in South Sudan, but in Kampala, one of the busiest city you can imagine for a child pushed out of her home by conflict.

“Daily bread wasn’t graceful—it was a battle,” she says, half-smiling.

“If I didn’t sell, we didn’t eat.”

Life gave her a lemon—and she couldn’t even afford to make lemonade.

To make things worse, her elders saw her as the family’s best investment, as if poverty were feeling lonely.

“A suitor was waiting; charming, healthy, and nearly four times my age,” she says with dignity, imitation.

“They thought marrying me off would buy the rest of my siblings a ticket out of misery.”

In truth, it was a heartbreaking economic strategy covered in cultural expectations, despite her interest in going to class like any child in a peaceful society. Education was a luxury she dreamed of but couldn’t afford. Iinstead, she battled a marriage proposal from the elders to an over-40-year-old man.

Thanks God! “Search appeared when I needed mental, physical, and financial support to complete my secondary education,” she asserted with a deep breath.

“The skills I gained will be the tool to help me see my college journey”.

That is Nyakang’s hopes, similar to those of thousands of children today at IDP camps, refugee settlements, orphanages and those living on the streets, paying the price of conflict they know nothing about.

The conflict from 2013 to 2016, the relentless situation in South Sudan, did not just steal her childhood. It stole her stability, her schooling, and every fear of certainty. Her family, like many others, faced the brutal triad of poverty, unemployment, and persistent displacement.

“I became an adult before I even knew how to spell my mother’s name,” she jokes. But where tragedy brewed, change also emerged.

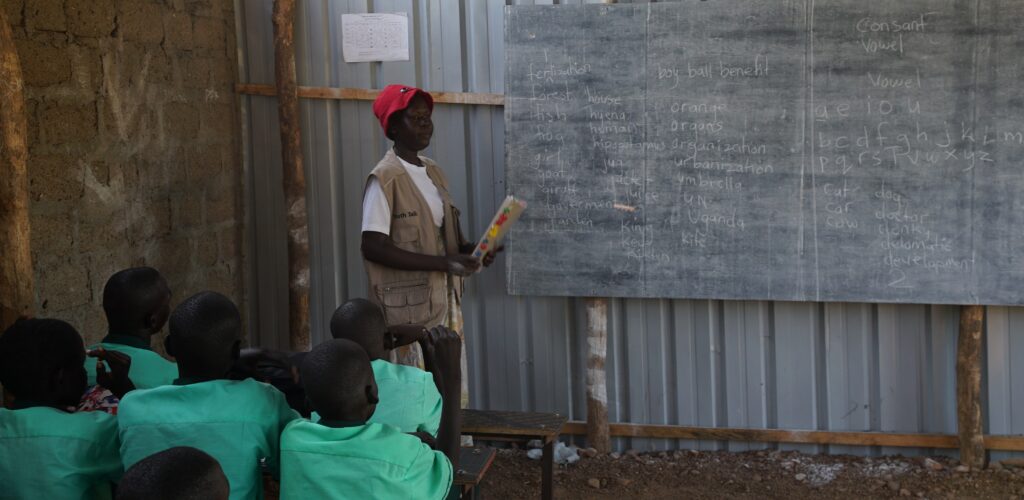

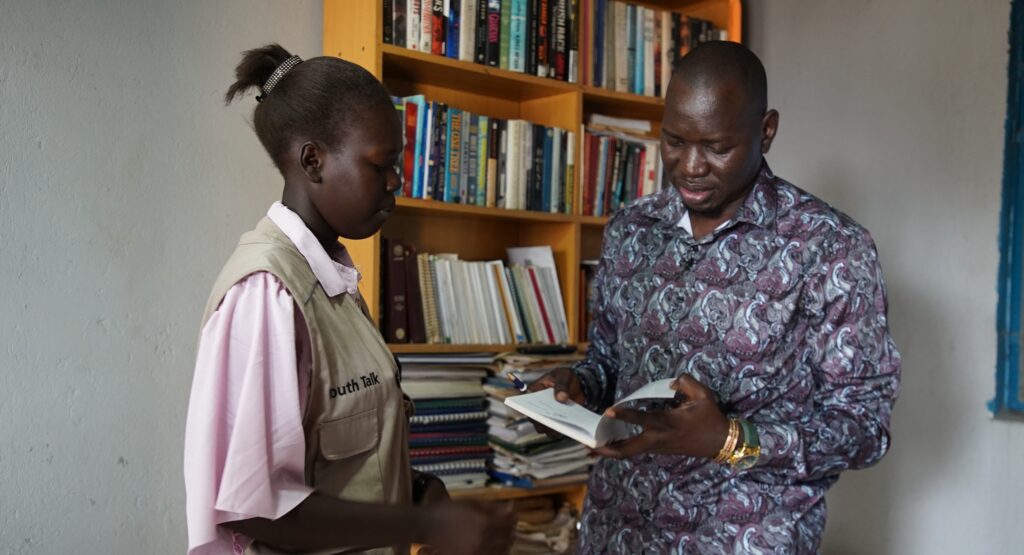

The Youth-Talk project, a Search for Common Ground’s regional youth-led initiatives, implemented in South Sudan, Mali, the Central African Republic (CAR), and Kenya, was the turning point in Nyakang’s story. From hawker to hope-dealer, she joined as a participant. Later, Nyakang transitioned to a volunteer, sharing her time between Search and Seed of Hope Primary School.

Her mission? To empower other young people, particularly those packed in the margins of Mangateen Camp, where IDPS wait, not just for NGOs’ support, but for recognition.

“I have nothing to offer,” she says, eyes steady, “but the skills and opportunities Search gave me. Those, I can pass on.”

It sounds simple, but in a country where trauma is passed down like inheritance, sharing knowledge and empathy is nothing short of ground-breaking. Through conflict management, perception and perspective training, and physical and mental education, Nyakang is reshaping how the next generation sees peace as a privilege and practice.

Her time in Seed of Hope Primary School isn’t just about handing out crayons and quoting peace slogans.

“Our community carries wounds,” she explains.

“And these wounds grow deeper when no one explains them.”

For her, the classroom is more than a blackboard and chalk; it’s a workshop for tolerance, where every child is a case study in potential. Nyakang became a mentor, counsellor, and big sister, not in the “blood family group” way. She listens with empathy when no one else will, intervenes when parents are far from the young ones, and challenges toxic narratives before they take root. “Wrong perspectives begin early,” she warns. “I’m here to ensure they don’t become dangerous.”

Over the years, Nyakang’s activism has gone beyond Mangateen. Through dialogue circles, youth forums, and intergenerational debates, designed activities of the Youth-Talk project, she has become a voice for the unheard. She’s not the typical microphone-grabbing advocate but more of a conversation starter with substance.

“Even in silence, we carry stories,” she says.

“But I prefer to tell mine out loud.”

Among her peers at Search, she has found a tribe, an odd mix of the hopeful and the hardened. “Some of us are orphans. Others have slept more nights on the streets than in beds. And some,” she adds with a playful glance, “are born to cause constructive trouble”.

Youth-talk participants come from hard-to-reach communities with various cultural differences, yet each has a trauma story behind a smiling face. Still, together in diversity, they are rewriting the narrative of South Sudanese youth, on-air, in schools, community spaces, and youth forums.

“It’s always pain and misery,” Nyakang admits, “but we have the tools to change things. If not today, you will feel the impact in a few years.”

She says it’s not like a politician making promises, but like someone who’s carried the weight of that delay in realising peace and reconstruction in South Sudan.

What makes Nyakang’s story both painful and powerful is not just what she overcame, but what she chose to become. She could have disappeared into the background, folded under pressure, or accepted her fate as a child bride. Instead, she became a mirror for others, reflecting their dignity, potential, and pain with empathy and enthusiasm.

In a nation exhausted by cycles of war and whispers of broken promises, Nyakang is not waiting for peace to be delivered from a presidential speech or foreign mission. She’s planting the seeds right in the camp where her adolescence was interrupted. And for every girl in South Sudan who sells snacks in the heat, dodging disappointment and indebted to cultural stereotypes, Nyakang’s power as a girl is a reminder that once a purpose emerges, empowerment follows, and solutions are drawn from within the communities that still marches toward meaning and hope in the solidarity of those in despair.

Nyakang, 21, today, showed interest in breaking barriers, speaking out, and staying among the vulnerable to continue supporting the community she respected with potential.