Health officials in South Sudan are warning of a rise in obstetric fistula cases, blaming delayed access to maternal care and widespread child marriage.

The concerns were highlighted during the national commemoration of the International Day to End Obstetric Fistula on Friday in Juba, where officials reaffirmed commitments to eliminate the condition by 2030.

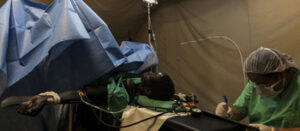

Dr. Anthony Lupai, director of Juba Teaching Hospital, said the country remains “badly hit with the burden of fistula,” a condition caused by prolonged, obstructed labor without medical intervention.

“We are here not to celebrate but to observe and reflect,” Lupai said. “This condition points to many things that are not going well — like inadequate health infrastructure, poor access to care and social practices like early marriage.”

Fistula, a preventable and treatable condition, creates a hole between the birth canal and the bladder or rectum, leading to chronic incontinence. Women with the condition often face severe medical and psychological consequences, including social rejection.

“We ask ourselves why we have more cases in South Sudan than in the rest of the world,” Lupai said. “It is not just about health workers. It is about access. You can have doctors and nurses, but if the woman cannot reach the facility on time, she suffers.”

Lupai stressed that ending fistula requires more than medical care — it demands political will, infrastructure, stability and community involvement.

“We need everyone — partners, media, government, chiefs and churches — to act. If we are to eliminate fistula by 2030, it will not happen through words but through real, coordinated actions,” he said.

Dr. Janet Michael, director general for midwives and nurses at South Sudan’s Health Ministry, said an estimated 6,000 women in the country are living with untreated fistula.

“Some women arrive at hospitals after the baby has died, and the damage is already done,” she said. “Many of them were denied timely care due to long distances, lack of transport or harmful beliefs that every woman must deliver at home.”

She linked many cases to unskilled home deliveries and harmful social norms, including the belief that cesarean sections are unnecessary or shameful.

“We cannot talk about ending fistula without talking about ending child marriage,” Michael said. “Forced and early marriage exposes girls to childbirth before their bodies are ready, and that leads to fistula.”

Dr. Yusuf Deng, a Health Ministry representative, urged stronger prevention measures.

“To end fistula by 2030, we must focus on prevention. That means putting an end to child marriage and educating our communities,” Deng said.

He called on lawmakers to enforce laws and civil society to raise awareness.

“We cannot cure our way out of fistula — we must prevent it,” he said.

In December, the Norwegian Embassy in Juba announced an additional $3.6 million in funding to the United Nations Population Fund to support sexual and reproductive health initiatives in South Sudan, with about $2.2 million specifically allocated for obstetric fistula treatment.

South Sudan has an estimated backlog of 60,000 fistula cases, with fewer than 1,000 women treated so far. The new funding is expected to help more women regain health and dignity.

The event ended with officials and community leaders pledging to eliminate fistula by 2030.

“Let us help our daughters and sisters give life without harm,” Lupai said. “Let them enjoy being women and mothers without the pain of fistula.”