South Sudan’s President Salva Kiir removed the country’s long-serving chief justice and Supreme Court president in a surprise presidential decree announced on state broadcaster SSBC on Wednesday night.

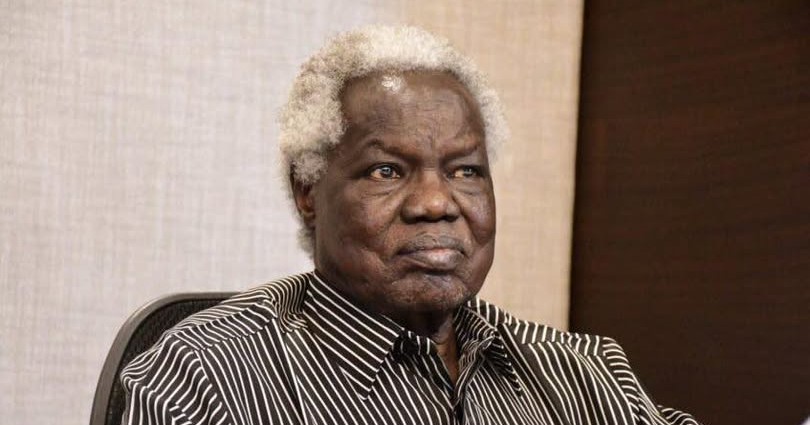

Chan Reec Madut, who had served as chief justice for more than 13 years, was replaced by Benjamin Bak Deng. Deputy Chief Justice John Gatwech Lul was also dismissed, with Laku Trankilo Nyumbi named as his successor.

No reason was given for the removals.

Under South Sudan’s 2011 constitution, the president may dismiss justices under certain conditions.

Article 135(2) states that judges “may be removed by an order of the president for gross misconduct, incompetence, or incapacity upon the recommendation of the National Judicial Service Commission.”

The constitution also requires Supreme Court justices to be appointed by the president “upon the recommendation of the Judicial Service Commission” and approved by a two-thirds majority in the National Legislative Assembly.

However, the law does not set a term limit for the chief justice.

Madut was appointed by Kiir in August 2011, shortly after South Sudan gained independence from Sudan. Before his judicial role, he served as deputy chair of the Southern Sudan Referendum Commission, which oversaw the independence vote, and chaired the Southern Sudan Referendum Bureau in Juba.

Judiciary challenges and criticism

Madut’s tenure was marked by persistent challenges in the judiciary, including allegations of insufficient independence from the executive. Observers have cited shortages of judges, poor infrastructure, and limited training for judicial staff, as well as concerns over corruption and political interference.

In recent months, Madut faced growing pressure. Two months ago, a group of South Sudanese lawyers petitioned Kiir to dismiss him, accusing him of failing to deliver justice.

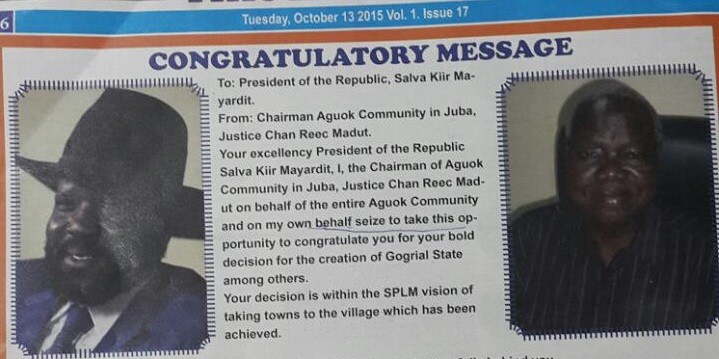

His neutrality was first questioned in October 2015 when he publicly endorsed Kiir’s controversial decision to create 28 new states, replacing the constitutionally recognized 10, before the matter was legally challenged.

Madut published a congratulatory message in Juba’s This Day newspaper, expressing support on behalf of his Dinka Aguok community and himself.

In July 2023, he drew further criticism for attending a political rally organized by the ruling Sudan People’s Liberation Movement (SPLM) in Wau, raising fresh concerns over judicial independence.

Political context

Madut’s dismissal comes amid the ongoing detention of opposition leader and First Vice President Riek Machar, who has been under house arrest since March 26. Authorities say Machar will face trial over alleged involvement in violence in Nasir, Upper Nile State.

Reaction to Madut’s dismissal

Dr. Geri Raimondo, a prominent lawyer, legal scholar, and former judge in South Sudan’s judiciary, told Radio Tamazuj that the appointment or dismissal of the Chief Justice and his deputy must be recommended by the Judiciary Service Commission before presidential approval.

“If this appointment came directly from the president, then it is a violation of the constitution. But if it followed the recommendation of the Judicial Service Commission, then it would be constitutional,” Raimondo said.

Under South Sudan’s Judicial Service Act, the Chief Justice chairs the Judicial Service Commission, which includes the deputy chief justice, the justice minister, the finance minister, the chair of the National Assembly’s justice committee, the dean of the University of Juba’s law school, the bar association president, and Supreme Court justices.

“They are the ones who should recommend who is competent to serve as Chief Justice or deputy,” Raimondo said.

He urged the new Chief Justice—whom he described as experienced—to push for judicial reforms, improve working conditions for judges, and root out corruption.

“Corruption is rampant in the judiciary. We need the people of South Sudan to reject it and allow judges to work independently,” he said.

Raimondo expressed hope that the new leadership would implement recommendations from past judicial reform efforts, noting that both the incoming Chief Justice and his deputy had served on a judiciary reform committee.

Ter Manyang Gatwech, a civil society activist, said former Chief Justice Chan Reec Madut faced long-standing tensions with junior judges, some of whom accused him of stifling their professional growth and lacking independence.

“Two months ago, lawyers petitioned for his removal,” Manyang said. “The judicial system in South Sudan is not trusted—many prefer customary law over the formal courts, which shows a crisis of confidence.”

He cited political interference in the judiciary, suggesting Madut’s removal could be linked to upcoming high-profile cases, including the potential trial of First Vice President Riek Machar.

“Maybe they wanted someone who would align with the president’s interests,” Manyang said. “South Sudan’s judiciary lacks independence—its decisions are often seen as politically influenced.”

The 2018 peace agreement mandated judicial reforms, including the appointment of new judges and training for fresh law graduates. However, activists say progress has been slow.