In most functioning democracies, political office is regarded as a solemn responsibility—a duty to serve the public with integrity and accountability. In South Sudan, however, public office has devolved into a vehicle for accumulation rather than administration. What was once a noble liberation movement has mutated into an instrument for personal enrichment, while most citizens endure relentless suffering under a regime of systemic neglect, tribal exclusion, and authoritarian control.

From the earliest resistance against marginalization by successive Khartoum regimes, South Sudanese leaders and intellectuals have consistently advocated for equality, federalism, and development. These were not the demands of rebels seeking power, but of a people denied basic services, subjected to cultural erasure, and economically marginalized for generations.

The First Sudanese Civil War (1955–1972) was more than an armed rebellion—it was a cry for justice and dignity. During this period, five successive Sudanese governments came and went without addressing the Southern Question. Only in 1972, through the Addis Ababa Agreement signed between President Jaafar Nimeiri’s government and the Southern Sudan Liberation Movement led by General Joseph Lagu, did a breakthrough emerge. The 1972 Peace Agreement helped secure significant gains: the establishment of the University of Juba, the development of Juba International Airport, a regional parliament, and new government complexes. These achievements were realized despite the limited national budget of the time.

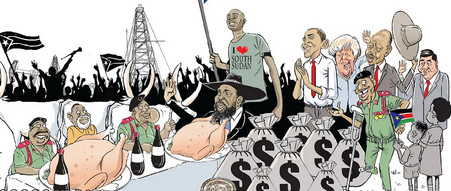

Today, with a national budget exceeding $2 billion, South Sudan should be flourishing. Instead, the country is crumbling. Civil servants have gone unpaid for over a year. Infrastructure is in a state of decay. Schools and hospitals are in ruin, and roads are nearly impassable. As the elite amass wealth and stash public funds in offshore accounts, ordinary citizens survive through humanitarian aid, evidence of a government that has abdicated its fundamental responsibilities.

The Sudan People’s Liberation Movement (SPLM), which recently marked 42 years since its founding, now commemorates this milestone not with reflection, but with elitist celebration. The movement that once gave hope to the marginalized, from Nimule to Wadi Halfa, has lost its ideological clarity and moral purpose. Today, it is driven not by the ideals of justice and equality, but by an insatiable thirst for power and privilege.

The roots of the SPLM’s internal rot trace back to its 1991 split. At that time, a faction led by Dr. Riek Machar called for the self-determination of the South Sudanese people, while others insisted on maintaining a united Sudan. The split revealed deep ideological rifts that have since widened. The movement became increasingly intolerant of dissent. Criticism of the leadership is treated as treason. Internal democracy is nonexistent. This culture of repression has spilled over into the institutions of state, where violence and authoritarianism have replaced dialogue and inclusion.

Juba, under SPLM rule, functions less as a national capital and more as a militarized command center. The government replicates the wartime structures of centralization and impunity. The prevailing mindset among the ruling elite is that their participation in the liberation war grants them a perpetual license to exploit the state. This logic has brought South Sudan to the brink.

Rather than building a peaceful, democratic, and inclusive state, the SPLM-led government has fueled insecurity, sanctioned tribalism, and enabled gross human rights violations. Public institutions are captured by ethnic favoritism. Arbitrary arrests, enforced disappearances, and extrajudicial killings are routine. In some cases, the regime has even hired foreign mercenaries to suppress dissent, violating the nation’s sovereignty and shedding the blood of its people.

South Sudan has signed multiple peace agreements, including the Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA) and the Revitalized Agreement on the Resolution of the Conflict in South Sudan (R-ARCSS). Each of these frameworks aimed to transition the country toward democracy and stability. Yet, the greatest obstacle has remained constant: the SPLM elite. Entrenched in tribal loyalty and committed to preserving the status quo, they have consistently sabotaged the implementation of these agreements. Even internal party reforms—such as conducting primary elections—are stifled, with party politics extended to dominate national governance.

Salva Kiir epitomizes this dysfunction. He has normalized a culture of arbitrary appointments and dismissals, endlessly recycling the same individuals in a purported search for competence, without acknowledging that his own leadership is the root cause of the country’s stagnation. Rather than building resilient institutions, his administration has systematically hollowed them out, turning governance into a patronage system.

Reform-minded leaders like Dr. Riek Machar, who played a central role in securing South Sudan’s right to self-determination, are treated as threats rather than partners in nation-building. Dr. Machar’s consistent advocacy for institutional reform has been met with persecution. During the 2013 conflict, Uganda’s President Yoweri Museveni deployed troops to prop up Kiir’s regime. More recently, under pressure from Kampala, Dr. Machar was placed under de facto house arrest. Uganda’s involvement in South Sudan’s internal affairs is not motivated by peace, but by the protection of its economic and strategic interests—interests that are fundamentally at odds with South Sudan’s democratic aspirations.

The SPLM’s legacy will not be defined by the duration of its rule, but by what it has delivered—and tragically, it has delivered only poverty, paralysis, and pain. Its leaders have weaponized the liberation struggle as a shield against accountability, using past sacrifices to justify present-day oppression.

But the people of South Sudan are not passive. They are watching. They are remembering. And they are yearning for change. The time has come to dismantle the toxic culture of militarism, tribal supremacy, and impunity that has captured the state. The country must move beyond the politics of liberation and embrace a new politics—one grounded in service, democratic values, and integrity.

South Sudanese citizens deserve more than recycled slogans and ceremonial independence. They deserve genuine freedom, accountable leadership, and a future worthy of the sacrifices made by generations past.

The SPLM’s legacy will not be measured by how long it ruled, but by what it delivered—and tragically, it has delivered only pain, poverty, and paralysis.

The writer is a South Sudanese legal scholar, human rights Lawyer and he writes on governance, peacebuilding, and post-conflict reconstruction in Africa.

The views expressed in ‘opinion’ articles published by Radio Tamazuj are solely those of the writer. The veracity of any claims made is the responsibility of the author, not Radio Tamazuj.