South Sudan, the world’s newest nation, has grappled with civil and political conflict since gaining independence from Sudan just over a decade ago. Despite these challenges, the country holds significant investment and business potential.

Today, however, a persistent shortage of passport booklets is emerging as a serious barrier—not only to entrepreneurship, but also to education, healthcare access, and international engagement.

The Director General of Civil Registry, Nationality, Passport and Immigration (CRNPI), Maj Gen Elia Costa Faustino, recently announced that passport booklets of all categories were currently unavailable in government stock. He attributed the shortage to delays in settling debts owed to the foreign company contracted to supply the documents.

As a result, traders engaged in cross-border commerce were missing regional fairs and expos, students with confirmed scholarships were unable to travel abroad, and critically ill patients who require specialized medical treatment outside the country, remain stranded.

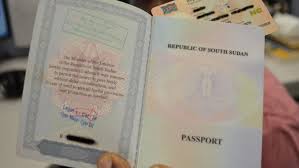

South Sudan gained independence in July 2011, becoming the world’s 193rd recognized nation. The government began issuing national identity certificates and passports to its citizens as part of building foundational state institutions.

With support from the International Organization for Migration (IOM), the new government contracted a German consultancy firm, Muhlbauer, to design, print, and produce national identity cards and passport booklets. The partnership marked a major step toward establishing a civil registration and documentation system.

In July 2023, Philip Kuch, the Assistant Director of Finance at CRNPI, told reporters in Juba that the Ministry of Finance and Planning had settled the US$1.7 million debt owed to Muhlbauer. The payment enabled the resumption of passport and national ID card printing.

“We received 10,000 passport booklets last week, and we have now received an additional 20,000,” Kuch said at the time. “We still have 182,000 booklets to be delivered, which should take us to the middle of next year.”

Despite these assurances, the supply proved insufficient, and shortages soon re-emerged, once again disrupting services across the country.

In August 2024, CRNPI announced the indefinite suspension of passport and nationality card issuance, citing a system failure caused by the expiration of printing software. Former CRNPI Director Maj Gen Simon Majur Pabek acknowledged public frustration and apologized for the disruption.

“I understand that many of our citizens urgently need passports and national identity documents for travel, studies, and medical treatment abroad,” he said.

“We apologize for the lack of prior notice and assure the public that the system will be repaired shortly. The issue is similar to a software failure that requires complete renewal, and we are working with our partners to address it.”

Pabek made the remarks while addressing angry citizens gathered at the Department of Nationality, Passport, and Immigration in Juba, who accused officials of poor service delivery and lack of transparency.

The Government of South Sudan issues four types of official travel documents, each serving a distinct purpose:

Ordinary Passport (Blue): Issued for general travel, tourism, education, and employment abroad. It is valid for five years and is the most commonly used passport.

Diplomatic Passport (Red): Issued to senior government officials, including the President, vice presidents, ministers, ambassadors, MPs on official missions, and senior judicial officers. Holders enjoy diplomatic privileges such as visa exemptions in certain countries and priority immigration clearance.

Official/Service Passport (Green): Issued to government employees and civil servants traveling abroad on official duty. It is not valid for personal travel and becomes invalid once the holder’s official assignment ends.

Emergency Travel Permit: Issued to South Sudanese citizens who lose their passports abroad or face urgent travel circumstances. It is usually valid for return travel or short-term movement, often restricted to neighboring countries, unless special authorization is granted.

According to Africa Press, South Sudan’s passport ranked 97th globally in 2025 on the Henley Passport Index, down from 73rd in 2024. In 2024, South Sudanese citizens could travel to 83 destinations visa-free or with visa-on-arrival; by 2025, that number had fallen to just 41.

The decline has been attributed to shifting visa policies by partner countries, reduced international travel agreements, ongoing political and security instability, and the detention and trial in a special court of the country’s First Vice-President, Dr Riek Machar, Petroleum Minister Puot Kang Chuol, and six other senior party officials.

Within East Africa, Kenya ranks 73rd globally, offering visa-free access to over 70 countries, followed by Uganda (76th, 67 destinations) and Ethiopia (96th, 44 destinations). South Sudan and Sudan both rank 98th, with access to only 41 destinations each.

South Sudan began issuing internationally recognized biometric electronic passports in January 2012. The documents were officially launched by President Salva Kiir on January 3, 2012 in Juba and comply with the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) standards. They carry a five-year validity.

To obtain a passport, a citizen must first possess a nationality identification certificate. Yet for many South Sudanese, recurring shortages have become a symbol of systemic failure rather than temporary disruption.

Political analyst John Bith Aliab argues that the crisis extends far beyond administrative delays.

“This recurring crisis, now familiar to citizens at home and abroad, is more than an administrative inconvenience,” he said.

“It is a symptom of deeper governance and planning failures that deserve honest public discussion.”

Students continue to miss scholarship opportunities, businesspeople lose access to regional markets, and families face mounting uncertainty. CRNPI has faced similar criticism in the past, including a major booklet shortage in 2020 linked to unpaid debts to the same German printing company. Although services resumed in November 2021 after partial payments, further disputes caused additional disruptions in 2023 before being temporarily resolved in 2024.

Observers say the current crisis underscores the government’s continued failure to permanently secure and manage one of the country’s most essential public services—leaving South Sudanese citizens grounded while opportunities move on without them.

The writer, Ruot George, is South Sudanese journalist. He can be reached via email mutgeorge8@gmail.com

The views expressed in ‘opinion’ articles published by Radio Tamazuj are solely those of the writer. The veracity of any claims made is the responsibility of the author, not Radio Tamazuj.