Abstract

The assertion that Kapoeta East County in South Sudan’s Eastern Equatoria shares a border with Uganda is decisively contradicted by historical and cartographic evidence. A systematic review of colonial treaties, boundary commission reports, and ethnographic studies reveals that, since 1902, Kenya’s Turkana region and the contested Ilemi Triangle have consistently formed an uninterrupted buffer between Uganda and Kapoeta East. The Uganda Order in Council (1902), the Maud Line delineation (1903), the Kelly–Tufnell Boundary Commission demarcation (1914), and subsequent colonial surveys (including the 1938 Wakefield [“Red”] Line, the 1947 Blue Line, and the 1950 Sudanese Patrol Line) all confirm that Kapoeta East borders Kenya, not Uganda. Likewise, patterns of pastoralist movement among the Didinga, Toposa, Turkana, and Dassanech communities indicate connectivity toward Kenyan territory rather than toward Uganda. Contemporary scholarship (Leonardi 2020; Mburu 2003, 2006; Shayna and Niveditha 2024) further reinforces the finding that Uganda has never been part of the Ilemi frontier system.

Introduction

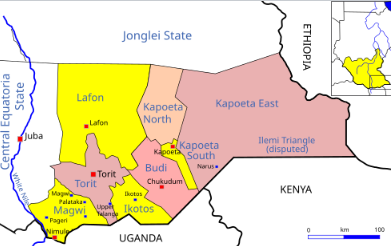

Kapoeta East County’s southeastern frontier is frequently misrepresented: for example, a 2020 Conflict Sensitivity Resource Facility profile erroneously claims that it borders Uganda. Official records indicate that Kapoeta East is bounded to the south by Kenya and to the east by Ethiopia. In contrast, Uganda’s border lies farther west, crossing the adjacent counties of Magwi, Ikotos, and Budi. Mburu (2003) aptly describes the Ilemi Triangle as “a triangular piece of land joining Sudan, Kenya, and Ethiopia… claimed at various times by all three, but never by Uganda” (p. 16). This article aims to categorically refute the claim made by the Kapoeta East County Commissioner that Kapoeta East borders Uganda via Kaabong District in Uganda. By reviewing historical, cartographic, and anthropological evidence, this analysis demonstrates that Kapoeta East County does not share a direct land boundary with Uganda. Furthermore, patterns of seasonal movement among the Didinga and Toposa pastoralists indicate that the corridor separating Uganda from Kapoeta East lies entirely within Kenyan territory, rather than across any direct border.

Colonial boundary formation

Colonial-era treaties and surveys consistently positioned Kenya between Uganda and the Sudanese frontier near Kapoeta East. The following sections review key boundary determinations that confirm this arrangement.

The Uganda order in council (1902)

In 1902, the British government issued an order transferring Uganda’s Eastern Province (then called Moroto or Rudolf Province) from the Uganda Protectorate to the British East Africa Protectorate (present-day Kenya). As Mburu (2003) observes, this Order “placed the Turkana basin within the Kenya Protectorate, permanently insulating Uganda from Sudan’s southeastern frontier” (p. 21). In effect, it created a Turkana buffer zone extending from Karamoja in Uganda to Kapoeta (then part of Anglo-Egyptian Sudan), eliminating any direct territorial contact between Uganda and Sudan.

The Maud Line (1902–1903)

In the 1902–1903 boundary survey led by Lieutenant Colonel Philip Maud, a meridian line was drawn to demarcate the frontier between Ethiopia and British East Africa (Kenya). This line effectively placed the Ilemi grazing lands under Anglo-Egyptian Sudanese administration on the west side while reaffirming Kenya’s claim along the southern frontier. Importantly, Uganda was entirely excluded from this delimitation. On Maud’s resulting map, the southwestern tip of Anglo-Egyptian Sudan lies well north of Uganda’s boundary, indicating that Uganda’s territory did not extend to Kapoeta East or the Ilemi region.

The Kelly–Tufnell Boundary Commission (1914)

The 1913–1914 Uganda–Sudan Boundary Commission (chaired by Captains Kelly and Tufnell) formally defined the Sudan–Uganda border along the Nimule–Magwi corridor, which lies far to the west of Kapoeta East. Recognizing the need to ensure Sudanese pastoralists had access to Lake Turkana, the commission included an “Ilemi Appendix” – a narrow wedge of territory administered through Kenya. Under this arrangement, Kenya – not Uganda – lay between Sudan and the Turkana basin to the southeast. The commission’s maps and reports from 1914 thus confirm that Uganda’s frontier extended along the Budi and Magwi counties well west of Kapoeta East.

Evolution of the Ilemi boundary

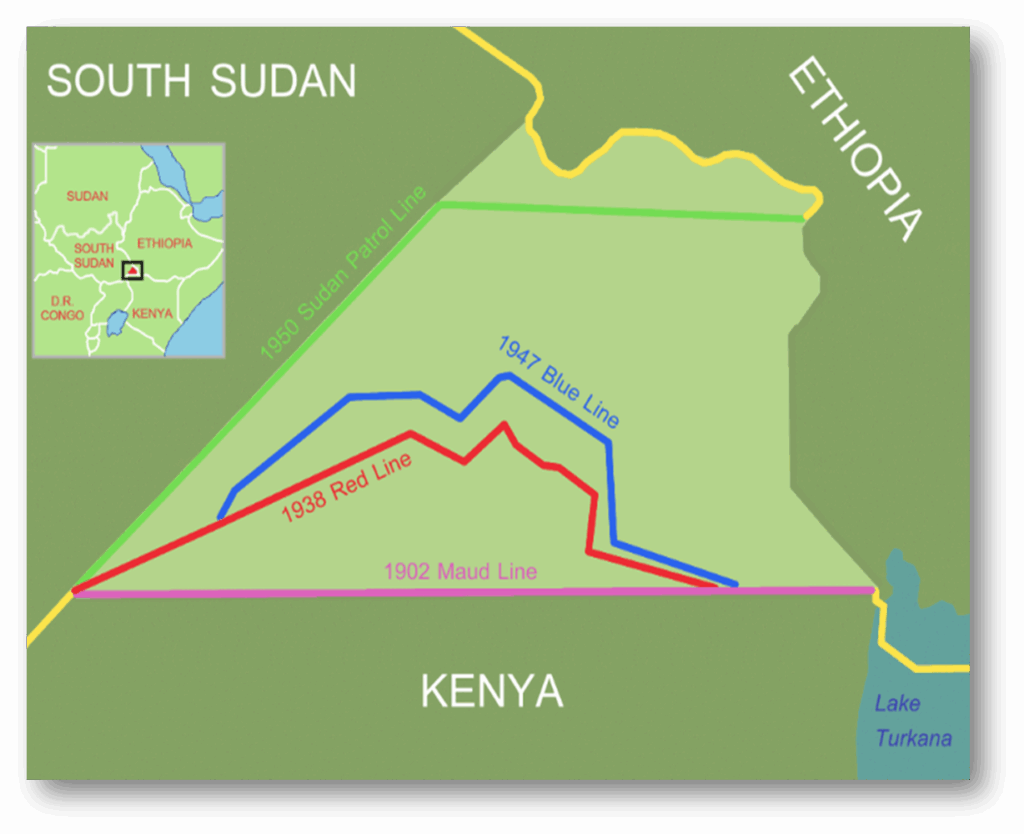

Figure 1 shows colonial-era demarcations in the Ilemi Triangle region: the Wakefield (1938) Line (red), the Blue Line (1947) (blue), and the Sudanese Patrol Line (1950) (green). These provisional boundaries were drawn to extend Kenya’s Turkana grazing areas northward, and importantly, none of them involves Uganda. Notably, the southern vertex of the Ilemi Triangle – Namoruputh on Lake Turkana – lies nearly 160 km north of Uganda’s present-day border. All these lines push the Sudan–British East Africa boundary deep into what is now Kenya’s territory, whereas the historical Uganda–Sudan boundary (west of the Ilemi region) remains far to the south of Kapoeta East.

Ethnographic context: The Didinga, Toposa, and Turkana

Pastoralist land-use patterns similarly underscore this separation. The Didinga people – indigenous to the Didinga Hills in present-day Budi and Kapoeta East – migrate seasonally northward toward Kapoeta and eastward into the western Ilemi Triangle during the dry season. Like the Toposa, their herding routes extend toward Kenya’s Turkana region rather than toward Uganda. As Leonardi (2020) notes, South Sudan’s borderland pastoralism is characterized by “localized mobility across inherited colonial frontiers,” especially in movements between Didinga and Turkana territories (p. 230). This mobility pattern demonstrates that Kapoeta East’s primary ecological and cultural contact zones lie with Kenya, reinforcing the conclusion that Uganda falls outside this frontier. Noonan and Bosco (2024) likewise identify the Turkana, Toposa, Didinga, and Dassanech peoples as the key pastoral communities involved in the Ilemi conflict-management system, explicitly noting the absence of any Ugandan community involvement. The lack of Ugandan actors in the Ilemi region further underscores that there is no shared border or grazing continuum between Uganda and Kapoeta East.

Cartographic evidence

Figure 2 (a 1970 U.S. Department of State map) depicts the Sudan–Uganda boundary (running from Nimule in the south to Morobo in the west). Importantly, Kenya (though not shown) lies southeast of the Ethiopia–South Sudan–Kenya tri-junction. This map confirms that Uganda’s northern border lies far to the west of Kapoeta East. Additionally, key geodetic markers defining the Ilemi frontier – such as the Sanderson Gulf, Namoruputh, Lokitaung, and Mount Lorienatom – all fall within Kenya’s Turkana–Ilemi zone (Kenya Survey Department 1950). Both colonial and modern maps show that Uganda’s northern boundary terminates well south of these markers, with Kenya’s Turkana District occupying the intervening space. Shayna and Niveditha (2024) reaffirm that the Ilemi Triangle dispute remains a tripartite issue involving Kenya, Ethiopia, and South Sudan, explicitly noting that “Uganda has never been part of the contestation” (p. 67). In sum, the cartographic record consistently places Uganda’s border hundreds of kilometers west of Kapoeta East, whereas Kenya’s frontier runs directly along Kapoeta East’s southern edge.

Discussion

A synthesis of historical, legal, and ethnographic evidence leads to a single, consistent conclusion: Kapoeta East County has never shared a land boundary with Uganda. The 1902 Uganda Order in Council effectively removed any Ugandan claim to the Turkana basin, and subsequent colonial surveys and demarcations explicitly positioned Kenya’s Turkana region between Uganda and Sudan. Likewise, the eastward pastoral migrations of the Didinga and Toposa confirm that Kapoeta East’s frontier connects only with Kenya. As Leonardi (2020) observes, the Sudan–Uganda boundary has long been anchored around Nimule and the White Nile in the west, whereas Kapoeta East lies within a Kenya–South Sudan–Ethiopia tri-border region centered at Namoruputh. No credible contemporary evidence supports the claim that Kapoeta East borders Uganda. Certain humanitarian profiles (for example, the Conflict Sensitivity Resource Facility county profile, 2020) erroneously list Kapoeta East as adjacent to Uganda, but these statements contradict the historical and cartographic record. In fact, the only South Sudanese counties contiguous with Uganda are Magwi, Ikotos, and Budi, all located well to the west of Kapoeta East. In every case – from treaties to surveys, maps, and ethnographic accounts – the evidence is unanimous that Uganda’s frontier skirts western Equatoria all the way to Didinga territory and does not touch Kapoeta East.

Conclusion

Based on over a century of treaties, maps, and ethnographic research, it is indisputable that Kapoeta East County does not border Uganda. Rather, Kenya’s Turkana region—including the contested Ilemi Triangle—acts as the legal, ecological, and administrative buffer between Uganda and Kapoeta East.

The Didinga people, whose homeland lies in the Didinga Hills of Budi County (South Sudan), maintain strong historical ties to the Turkana people of Kenya. Their oral traditions record migration from north of Lake Turkana (or possibly Ethiopia), and ethnographic sources confirm that the Turkana are among their traditional neighbors. During dry seasons, Didinga (and Toposa) pastoralists graze in western parts of Kenya’s Ilemi Triangle, demonstrating resource‑use proximity, not formal territorial sovereignty.

Importantly, the Ilemi Triangle itself remains a disputed borderland. While South Sudan claims it (inheriting Sudan’s claim), Kenya has administered the territory de facto for decades. Colonial-era lines—the “Maud Line” (1902) and subsequent patrol demarcations—were drawn primarily to manage pastoral mobility rather than establish fixed nation-state borders. The encroachment of one community’s livestock or settlement into another’s territory has historically provoked tension, conflict, and violence, highlighting the critical importance of clearly defined boundaries.

Any claim that Kapoeta East shares a border with Uganda misrepresents both legal geography and pastoral realities. The true tri-junction of Kenya, South Sudan, and Ethiopia lies at Namoruputh on Lake Turkana, well north of Uganda’s boundary. Meanwhile, Budi County legitimately borders Uganda’s Kabong District, reinforcing that Kenya’s Turkana/Ilemi zone separates Kapoeta East from Uganda.

Correcting public discourse and humanitarian profiles to reflect these nuanced realities will strengthen cross-border coordination, prevent policy misalignment, reduce intercommunal conflict, promote peaceful coexistence amongst neighboring communities, enhance local governance, and improve intervention effectiveness.

References

- Collins, R. O. (1962). Sudan–Uganda boundary rectification and the Sudanese occupation of Madial, 1914. Uganda Journal, 26(2), 145–159.

- Conflict Sensitivity Resource Facility. (2020, March 22). Kapoeta East County, Eastern Equatoria State. Retrieved from https://csrf-southsudan.org/county_profile/kapoeta-east/

- Kenya Survey Department. (1950). Administrative maps of the Northern Frontier District and the Ilemi Patrol Zone. Nairobi: Government Printer.

- Leonardi, C. (2020). Patchwork states: The localization of state territoriality on the South Sudan–Uganda border, 1914–2014. Past & Present, 248(1), 209–245. https://doi.org/10.1093/pastj/gtaa018

- Maud, P. (1904). The Abyssinian boundary. The Geographical Journal, 24(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.2307/1776379

- Mburu, N. (2003). Delimitation of the elastic Ilemi Triangle: Pastoral conflicts and official indifference in the Horn of Africa. African Studies Quarterly, 7(1), 15–38.

- Mburu, N. (2006). International law and the doctrine of territorial sovereignty: An analysis of Kenya’s legal status on the Ilemi Triangle (Unpublished master’s thesis). University of Nairobi. Retrieved from https://erepository.uonbi.ac.ke/handle/11295/18221

- Moro, L. N., & Robinson, A. (2022). Key considerations concerning cross-border dynamics between Uganda and South Sudan in the context of the outbreak of Ebola, 2022. Social Science in Humanitarian Action Platform. DOI: 10.19088/SSHAP.2022.045

- Noonan, B., & Bosco, C. (2024). The dynamics of decision-making processes in sustainable conflict management in the Ilemi Triangle. International Journal of Social Science Research and Review, 7(4), 87–104. https://doi.org/10.47814/ijssrr.v7i4.2377

- Shayna, R., & Niveditha, M. (2024). Unresolved legacy: The Ilemi Triangle dispute. Journal of Conflict and Peace Studies, 12(1), 55–72.

- Tufnell, H. M. (1914). Report of the Uganda–Sudan Boundary Commission. Colonial Office Archives, Kew, London.

- United Kingdom Foreign Office. (1907). Anglo-Ethiopian Treaty, 1907. London: His Majesty’s Stationery Office.

- Wikipedia contributors. (n.d.). Kapoeta East County. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved November 12, 2025, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kapoeta_East_County

The writer is a concerned citizen and resident of Budi County. He can be reached via lokonyenaldo@hotmail.com.

The views expressed in ‘opinion’ articles published by Radio Tamazuj are solely those of the writer. The veracity of any claims made is the responsibility of the author, not Radio Tamazuj.