Since March 2025, South Sudan’s Council of Ministers—the highest executive decision-making body—has not convened, raising fears of a government breakdown. The last meeting took place before the detention of First Vice President Riek Machar and the escalation of political tensions.

Experts warn that the prolonged absence of cabinet meetings has left the country without a functioning government, threatening the fragile peace process and casting doubt on the feasibility of planned 2026 elections.

Here’s what you need to know.

Why has the Council of Ministers stopped meeting?

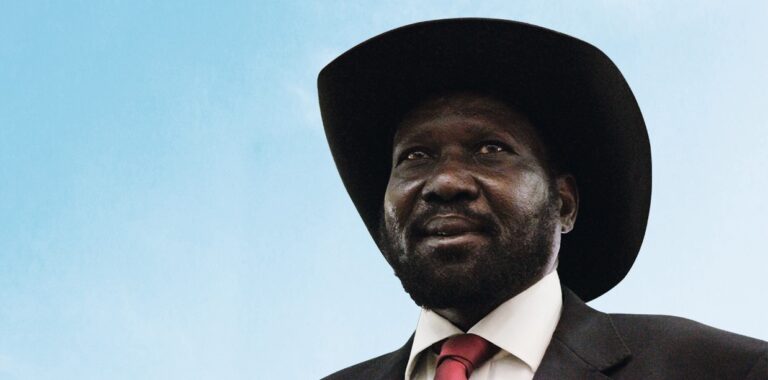

The Council of Ministers, chaired by President Salva Kiir Mayardit, has not met since March 2025. Analysts link the paralysis to political tensions and the detention of Riek Machar, the First Vice President and leader of the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement-In Opposition (SPLM-IO).

Dr. Abraham Kuol Nyuon, a political science lecturer at the University of Juba, says Machar’s arrest and the replacement of senior officials have created divisions within the government. He explains that this has caused unrest among senior officials, possibly making the president hesitant to hold meetings for fear of opposition.

Ter Manyang, a civil society activist, agrees, stating that the arrest of Machar, who chairs the governance cluster, is a major reason. He adds that some of Machar’s allies are also out of the country, worsening the crisis.

What does this mean for South Sudan’s governance?

With parliament in recess for months and the judiciary underfunded, the executive was the last functioning arm of government. Parliament had just resumed sessions last week after a six-month break. Now, the cabinet’s inactivity means no major policies are being approved, no budgets are being passed, and ministers are left without direction.

Dr. Abraham Kuol warns that South Sudan has been operating without a functioning executive branch for several months. He emphasizes that no progress is being made under these conditions.

Dr. Remember Miamingi, a governance expert, adds that the constitutional order is collapsing, with power increasingly concentrated in the office of the president. This undermines checks and balances, leaving the country in a de facto autocratic state, he says.

How does this affect the 2018 peace deal and planned elections?

The 2018 peace agreement requires power-sharing between President Kiir’s faction and Machar’s SPLM-IO throughout the transitional period until elections scheduled for December 2026. But with Machar detained and his allies sidelined, key reforms—such as security sector restructuring, constitutional making process and transitional justice—have stalled.

Dr. Kuol warns that elections scheduled for December 2026 are now in doubt. He argues that their feasibility depends on whether the president is serious about holding them, saying the current stagnation makes it unlikely.

Dr. Miamingi adds that without a functioning cabinet, South Sudan cannot meet its international obligations, risking further isolation and loss of donor support.

What are the economic and humanitarian consequences?

The 2025/26 budget remains unapproved, forcing ministries and state-owned agencies to operate on emergency funds. Civil servants’ salaries are delayed, and public services such as healthcare and education are suffering.

Dr. Miamingi notes that vaccine distribution has halted and several humanitarian projects are frozen, with the most vulnerable populations paying the price.

Can South Sudan’s government function without cabinet meetings?

The answer is no. The Council of Ministers is not merely a symbolic institution—it is the engine of governance, constitutionally mandated to translate policies into action, approve critical national decisions, and ensure the state functions. Without it, South Sudan’s government is effectively paralyzed.

The Council’s role is enshrined in Article 109 of South Sudan’s Transitional Constitution, which designates it as the highest executive authority responsible for policy formulation, budget approval, and implementation of laws. Its paralysis means no new policies can be adopted and no budgets ratified.

What’s the way out?

Observers suggest three urgent steps. First, the unconditional release of First Vice President and opposition leader Riek Machar to restore trust in the transitional period. Second, a high-level dialogue under regional mediation by IGAD or the African Union. Third, the immediate resumption of cabinet meetings to revive governance and peace implementation.