A former South Sudanese lawmaker has called on the government to restore her nationality documents, months after the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights ruled that she was arbitrarily deprived of her South Sudanese citizenship and ordered the state to take corrective action.

Animu A. Risasi Amitai’s citizenship also became a subject of national controversy in 2021. President Salva Kiir revoked her appointment as a member of the Transitional National Legislative Assembly representing Morobo County in May 2021 shortly after she was nominated to parliament. She had been selected on the ticket of the umbrella group, Other Political Parties, under the country’s 2018 power-sharing agreement.

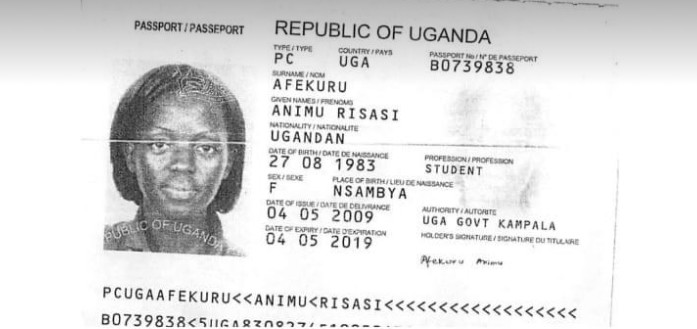

Her appointment at the time drew mixed reactions and sparked public debate across social media platforms, where several users questioned her nationality, alleging she was a Ugandan citizen. The Keliko community of Morobo County also formally rejected her appointment to represent Lujule Payam in the national legislative assembly.

Speaking to Radio Tamazuj on Wednesday, Animu A. Risasi Amitai said her nationality certificate and passport were withdrawn in 2018 following media reports that questioned her citizenship after she worked in the office of the then First Vice President, General Taban Deng Gai. She said immigration authorities acted without due process or any formal communication.

“I was arbitrarily deprived of my instrument of nationality,” Risasi said. “They withdrew my nationality certificate and my passport based on reports they had received in the media.”

She said when she asked immigration officials for reasons, they failed to provide any written explanation or court authorization. According to Risasi, the action violated South Sudan’s Nationality Act, which does not give immigration authorities the power to adjudicate nationality disputes.

Following the withdrawal of her documents, Risasi said she sought legal redress through the Juba High Court in 2019, but immigration authorities failed to appear in court. She later escalated the matter to the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights in 2021 after what she described as life-threatening developments.

The case was represented before the commission by the Institute for Human Rights and Development in Africa, a Gambia-based organization specializing in strategic human rights litigation. The African Commission subsequently ruled in Risasi’s favor, affirming her South Sudanese nationality and finding that several of her rights had been violated.

The decision was formally communicated to the South Sudan government on Aug. 2, 2025, granting it a 180-day compliance period ending on Feb. 2, 2026. However, Risasi said the government has so far failed to respond.

“We are five months in, and there’s been no communication, no reaction, despite our best efforts,” she said, warning that the silence is deeply concerning.

Risasi stressed that her case goes beyond her personal situation, highlighting the broader problem of statelessness in South Sudan. “Statelessness affects a lot of people, not just myself,” she said.

Risasi said she has always been South Sudanese, noting that, like many South Sudanese who lived in exile, she previously traveled on Ugandan documents before independence. She said those documents were returned after South Sudan became independent in 2011.

“For all intents and purposes, I’ve always been South Sudanese,” she said.

Risasi believes the accusations against her were politically motivated, noting that questions about her nationality only arose when she assumed senior political roles. “Every time this case came up, it was always connected to a political post,” she said, arguing that nationality was weaponized to limit her political participation.

She described the impact of losing her nationality documents as devastating, both practically and psychologically. She said she has been unable to travel, access formal employment, or even enter certain restricted areas due to the lack of government-issued identification.

“It’s like you’re in a sort of mental prison,” she said. “Your existence is basically wiped.”

Looking ahead, Risasi said she and her legal team would pursue further action if the government fails to comply with the African Commission’s ruling.

“What happens if they don’t implement? Do I just give up? That’s definitely not an option,” she said, adding that public advocacy and engagement with regional bodies would continue.

She called on South Sudan to use her case as an opportunity to address statelessness, especially after the country became a party to the 1954 and 1961 Statelessness Conventions.

“The right to nationality is non-negotiable,” Risasi said. “Access to nationality documents is a prerequisite to participate in the peace process, the democratic process, the census, and constitution-making.”

She urged authorities to bridge the gap between progressive laws and their implementation to ensure a more inclusive and governable society.

Immigration officials in Juba could not immediately be reached for comment.