As billions of South Sudanese pounds are allocated in South Sudan’s national budget, delayed salaries, underfunded clinics and weak revenue collection are leaving many citizens without basic services.

At 7 a.m., John locks the door of his small rented room and begins the long walk to work.

He is a civil servant in the capital, Juba. His government salary, when paid, barely covers food. Some months, he says, it does not come at all.

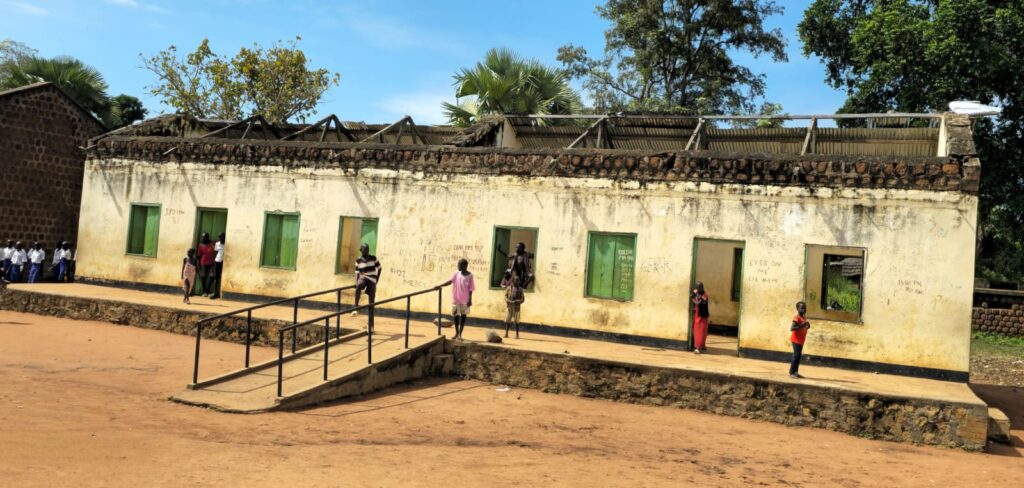

His children have missed school twice this term because fees were unpaid. At a public clinic last month, he was told to buy medicine from a private pharmacy because supplies had run out.

“If you go to a private hospital, you cannot treat yourself because it is expensive,” he said. “Even food is difficult. Sometimes you choose whether to eat or travel to work.”

On paper, South Sudan has an 8.5 trillion SSP national budget this year.

But for workers like John, that money rarely translates into functioning services.

Imbalances in spending

Government projections show expected revenues of about 7 trillion SSP from oil and taxes, leaving a deficit of roughly 1.5 trillion SSP.

Analysts say the problem is not only the size of the budget, but how it is executed.

Budget execution data reviewed by the World Bank shows sharp disparities between approved allocations and actual spending.

Infrastructure spending exceeded its approved allocation by more than 1,600%, while security overspent by more than 200%, according to the data. By contrast, the health sector used less than one-third of its approved budget and accountability institutions spent just 4%.

“The budget is a framework and, legally, institutions are not supposed to spend more than they were allocated because the budget is an act,” said David Santos Ruano, a senior public sector specialist at the World Bank.

“What we see in South Sudan is many institutions execute above their budget… Another institution under-executes a lot,” he added.

Under South Sudan’s Public Financial Management Act, spending beyond what parliament approves is illegal.

Inflation erodes allocations

Even where allocations rise in nominal terms, inflation and currency depreciation have eroded their real value.

Health funding increased in local currency terms, but fell sharply in real terms after the exchange rate weakened, reducing the sector’s purchasing power.

“You can say we are allocating more money, but it does not necessarily help because of the depreciation and exchange rate,” Santos said. “In real terms there was a reduction of 41%. Now, I cannot buy the same medicine with those SSPs — I can buy less medicine.”

For patients like John, that means empty clinics and higher out-of-pocket costs.

Revenue losses at the border

At the same time, economists say the government may be collecting far less tax revenue than it could.

One issue is the exchange rate used to calculate customs duties. South Sudan applies an official rate that is significantly lower than the market rate. Because import taxes are calculated based on the local currency value of goods, using a lower rate reduces the amount of tax collected.

For example, a $100,000 shipment valued at 1,500 SSP per dollar would be worth 150 million SSP at the market rate. At an official customs rate of 900 SSP, the same shipment would be valued at 90 million SSP. At a 10% duty, the government would collect 6 million SSP less.

“The exchange rate for customs is extremely low, and that reduces the possibility to collect the proper taxes in customs,” Santos said.

Across hundreds of imports, analysts say, such gaps could amount to billions of SSP — revenue that could otherwise fund salaries, medicine and schools.

Salaries and reforms

Globally, Santos said, wages and public debt servicing are treated as priority expenditures because they underpin public service delivery.

“In all countries, there are two main priorities for expenditure — wages and salaries, and public debt. These are the main priorities,” he said.

In South Sudan, however, salaries remain low, unpredictable and frequently delayed, directly affecting service delivery.

Finance Minister Dr. Baak Barnaba Chol has said the government is working to stabilise the economy. Last year, the cabinet approved an economic stabilisation and structural reform plan aimed at restoring fiscal discipline.

Measures include prioritising salary payments, limiting non-essential spending, expanding non-oil revenues, introducing value-added tax and cancelling non-statutory tax exemptions.

“Government will enforce absolute prioritisation of salaries,” the minister said. “Payments for non-essential claims and contracts will be limited.”

He added that exemptions on fuel, food imports and luxury goods would be reviewed to protect revenue collection.

Calls for accountability

Civil society groups say reforms must translate into visible improvements.

Edmund Yakani, executive director of the Community Empowerment for Progress Organization (CEPO), said civil servants continue to bear the brunt of weak budget discipline.

“We have seen civil servants operate without salaries,” he said. “Delay of salaries results in low performance, and that means services are not delivered.”

He urged lawmakers to prioritise schools, clinics, agriculture and basic infrastructure over administrative and security spending.

“We need transparency and accountability. We need budget discipline,” he said.

For John, the debate over trillions of pounds feels distant. What matters, he said, is regular pay, functioning hospitals and schools that remain open.

“If the salary comes on time,” he said, “life can move.”

Until then, South Sudan’s budget remains a set of figures approved in parliament but still out of reach for many of the people it is meant to serve.