There is a fundamental question of whether Sudan’s transition would succeed this time given the political dynamics since independence. For the optimists the recent uprising reflected an interlocking system of oppression in which racial, social, ethnic, regional and religious variances were transcended.

All Sudanese equally demonstrated regardless of their pressing issue that ranges from social, religious, political and economic disparities that have been structural for ages. This holistic picture of the Sudanese coming as one is rare and is an impetus to structural changes. However, pessimism is creeping in as some voices are emerging to claim that negotiations and consequently the upcoming transition is not as inclusive as the demonstrations.

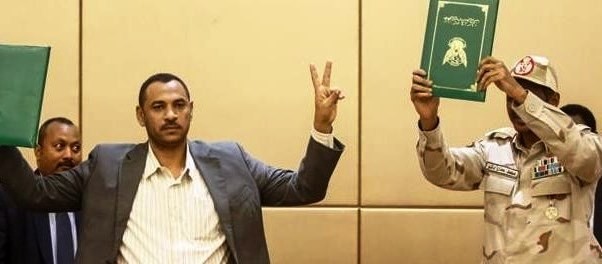

From the onset it should be noted that the December 2018 uprising was not the first although it has deposed the longest serving president in the history of Sudan. It remains nuanced in scope and magnitude and demands squarely captured in the phrase ‘freedom, peace and justice’.With the formation of the transitional authority some voices are pessimistic whether these three fundamentals would be met although the first six months is designated to address question of peace.

Peace in Sudan is easily pronounced than implemented or genuinely achieved. With a protracted history of firsthand state-induced violence through injustice, dismissive politics and direct repression for 63 years, the peace process would not be a walk in the park. The success of the Sudanese revolution is a direct result of an accumulation of structural and physical violence interlocking with immediate concerns such as lifting of subsidies shortage in bread among other economic woes. So within such dynamic it cannot be separated and the issues should not have been between parts of Sudan engaging other parts in peace.

Analyzing the recent uprising (Berridge, 2019) outlined how the deposed regime that has been preoccupied with repressing revolts at the periphery was caught unaware by a new periphery at the riverine center. Although, belittling the role of the peripheries in the revolution(s) but such a statement captures the reality today and ever since. The problem of Sudan has never been a technical question, but fundamentally a justice and rights question that hinges on the principles of rights and justice. Such problems are no in short of technical experts but in restoring rights. The recent demands by some regions for self-determination is not only a remedial solution to an unjust system but a demand for a right to a state that is accommodative. This is the question that the new rulers should try to decipher rather than to claim their tyranny as experts.

The Forces of Freedom and Change (FCC) as the main agent of change engaged the remnants of the regime and agreed on a minimalist approach to reform. It is deceptive to consider real change within the current dispensation that is highly securitized (securitization is when an issue is considered facing an existential threat and deserve to be secured). The Transitional Military Council has instituted itself as the guardian of the state heritage against unknown threats and as such imposed itself with a new role in governance. Interestingly the FFC agreed without questioning the logic of the army in politics that made Sudan the way it is.

Dr. Hamdouk is a reputable scholar and practitioner conversant with issues of democratization, constitutional making and economics among other relevant skills in governance. It is a good start but the problem of Sudan is not due to lack of capacity but more of lack of political will. Dr. John Garang de Mabior refers to the problem of the Sudan as of a country in search of its soul in the wrong place. What he meant is that the solution to Sudan’s foes is internal and by recognizing Sudan’s internal dynamics. Due to the perennial question to define who are the Sudanese (Africans, Arabs, Afro-Arabs) the main question in governance that is quintessentially methodological and should answer questions on how Sudan should be governed; is ever replaced by answering the who question (who should govern).

I reiterate Easterly (2013) assertion rejecting the fallacy considers ‘bad government is itself a problem amenable to technical solution’. It is empirical that ‘bad government suffers from a shortage of rights, not a shortage of experts’. Sudan suffers deeply entrenched injustice, lack of fundamental rights and as such a serious government should stem structural violence rather than stock experts and become preoccupied with questions of ‘who to govern’ more than how to restore justice and rights.

The leaked nominations so far reflect a new reality that Sudan is yet to be transformed. There are deliberate exclusion of minorities in the Sudan, including Christians, non-Arabs and non-Riverine, although Hamdouk is considered from the margins plus others, but real social dipartites are not bypassed and reflected by FFC in this coming transition. The logic of nominations suggests that there are no other experts existing outside the broadly defined parameters of Arabism, Riverine and Islam. I wish not to judge from the onset but a country that existed for more than 5000 years as Kush, Nubia and then the Sudan cannot be trapped within identity crisis all through.

With the structures, cultures and attitudes of violence all intact the upcoming transition would be questionable and may not achieve reforms that would transform Sudan. I have evidence beyond reasonable doubts that the new rulers are not different if not an extension of the old structures. To prove the doubtful wrong then after revealing the first tier of government that is largely imbalanced there is need to prove the merit of the revolution by transcending the social, economic, ethnic and other disparities that punctuated the Sudanese politics over the past 63 years. As Acemoglu and Robinson (2013) argued it is not about individuals but more of forging institutions that make impact. What transformed Europe is an institutionalized transformation not changes of individual bad rulers. Sudan has an opportunity to dispel structured injustice that captured the state for half a century. It is about the right transition or no transition.

The author Stephen Arrno is PhD candidate studying International Relations with focus on Conflict, Peace and Security in the Horn Region. He is reachable through saarno@usiu.ac.ke .

Acemoglu, Daron. and Robinson, James. (2013) Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity and Poverty. Profile Books: London

Berridge, W. (2019) “Briefing: The Uprising in Sudan”. African Affairs 1-3. African Royal Society: Oxford University Press doi: 10.1093/afraf/adz015

Easterly, William. (2013) The Tyranny of Experts: Economics, Dictators and The Right of the Poor. Basic Books: New York

The views expressed in ‘opinion’ articles published by Radio Tamazuj are solely those of the writer. The veracity of any claims made are the responsibility of the author, not Radio Tamazuj.