The renewed push by South Sudan’s SPLM-led transitional government to conduct general elections—particularly presidential ones—in 2026 has generated serious legal, political, and security concerns. While elections are often presented as the hallmark of democratic governance, in post-conflict societies like South Sudan, the timing and conditions under which they are held are just as important as the act of voting itself.

Conducting elections in 2026 without a permanent constitution, completed security arrangements, meaningful judicial reform, or a national population census would not only undermine the credibility of the electoral process but would also constitute a clear violation of the Revitalized Agreement on the Resolution of the Conflict in the Republic of South Sudan (R-ARCSS). Such a move would fall far short of the democratic standards set by the African Union (AU) and the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD).

Rather than consolidating peace, premature elections risk entrenching authoritarian rule, institutionalizing illegitimacy, and reopening pathways to violent conflict in a country that remains deeply fractured by years of war, political exclusion, and militarized governance.

Elections Are the End Point of the Transition, Not a Substitute for It

The R-ARCSS is explicit about the sequencing of the transition. Elections are not designed to compensate for unfinished reforms; they are meant to conclude a successful transitional process. The Agreement establishes a clear order of priorities, beginning with an inclusive and participatory constitution-making process that reflects the will of the South Sudanese people.

This must be followed by comprehensive security sector reform, including the unification, professionalization, and redeployment of armed forces under a single national command. Judicial and institutional reforms are then required to restore the rule of law and guarantee accountability. Only after civic and political space has been protected, a national population census conducted, and credible voter registration completed can elections legitimately take place.

Skipping these steps is not a minor procedural shortcut—it is a direct breach of the peace agreement that provides the legal foundation for the current transitional government. Elections held in violation of the R-ARCSS cannot produce legitimate outcomes. Instead, they risk delegitimizing the entire transition and collapsing the Agreement itself.

Judicial Reform Remains Largely Unimplemented

Credible elections depend on an independent and trusted judiciary capable of resolving electoral disputes impartially and peacefully. Yet judicial reform—one of the core pillars of the R-ARCSS—remains largely unimplemented.

Courts continue to lack independence, prosecutorial institutions remain unreformed, and there are no credible or transparent mechanisms for resolving electoral disputes. In such an environment, contested election results would have no lawful avenue for redress. History in South Sudan and across the region shows that when courts cannot arbitrate political disputes, those disputes are far more likely to be resolved through violence. Elections conducted without judicial guarantees do not strengthen democracy; they invite instability and deepen political mistrust.

Falling Far Short of AU and IGAD Democratic Standards

Regional and continental instruments, including the African Charter on Democracy, Elections and Governance and IGAD’s principles on democratic elections, establish minimum conditions for credible polls. These include the existence of a constitutional order accepted by the people, neutral and professional security forces, independent judicial and electoral institutions, equal political participation free from intimidation, and transparent electoral administration based on reliable population data.

South Sudan currently meets none of these requirements. Proceeding with elections under such conditions would not only undermine domestic legitimacy but would also set a dangerous precedent for democratic backsliding in the region, weakening hard-won norms governing post-conflict transitions in Africa.

Militarization of Politics and Electoral Insecurity

Security arrangements under the R-ARCSS remain largely unimplemented. Armed forces are neither unified nor politically neutral, and politics continues to be deeply militarized. Opposition parties operate under constant restriction, civic actors face harassment, and voters are routinely exposed to intimidation and coercion.

More troubling are ongoing reports of forced displacement of civilians perceived to support opposition groups, alongside allegations of aerial bombardment of civilian areas using military aircraft. Elections conducted amid active displacement, fear, and militarized control cannot be free, fair, or credible.

Experience from the African Union and the United Nations consistently shows that elections held in insecure environments often deepen conflict rather than resolve it.

No Census, No Repatriation, No Fair Representation

The absence of a national population census, combined with the failure to repatriate refugees and resettle internally displaced persons (IDPs), fundamentally undermines the principle of equal political representation.

Millions of South Sudanese remain displaced or living as refugees in neighboring countries, unable to register or vote from their constituencies. In a country where land ownership, ethnic identity, and political representation are deeply contested, such exclusion is not merely administrative—it is politically explosive.

An election that systematically excludes large segments of the population cannot be a unifying national exercise. Instead, it risks becoming a trigger for renewed conflict.

Responsibility of the Presidency

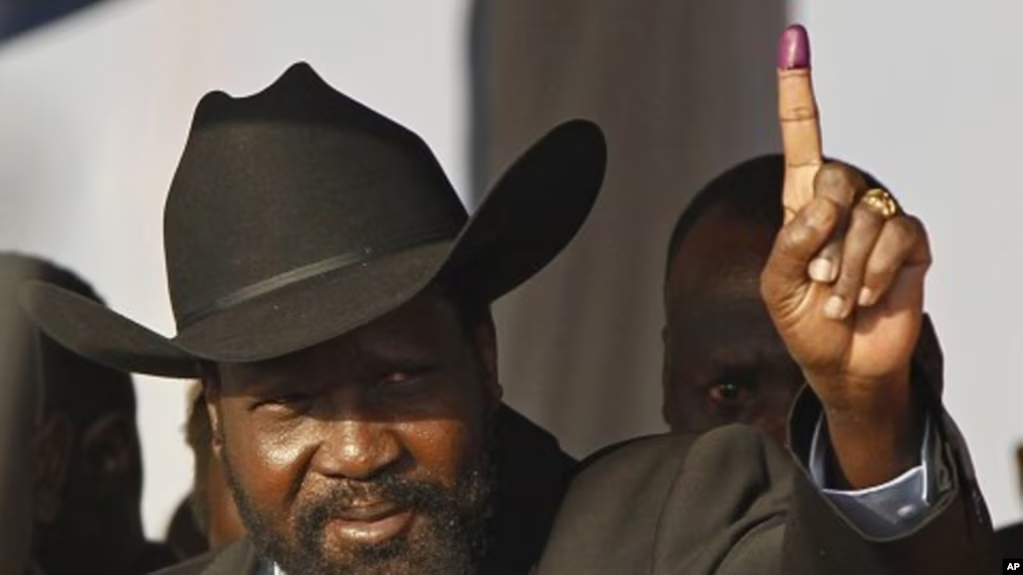

Responsibility for the failure to implement the R-ARCSS rests squarely with the current presidency. Rather than acting as a neutral guarantor of the transition, Salva Kiir and the SPLM have presided over repeated delays in constitution-making, selective implementation of security arrangements, failure to reform the judiciary, suppression of civic and political space, and continued concentration of power in the executive.

Pushing for elections under these conditions suggests an attempt to convert de facto power into electoral legitimacy without fulfilling the obligations of the peace agreement. This approach does not advance democracy; it entrenches authoritarian continuity under the appearance of constitutionalism.

What the International Community Should Do

For the United Nations, the African Union, IGAD, and international partners, endorsing premature elections would amount to legitimizing non-compliance with a binding peace agreement. It would undermine years of diplomatic engagement and weaken international norms governing post-conflict transitions.

International partners should insist on the full implementation of the R-ARCSS, condition electoral support on constitutional, judicial, and security reforms, demand the safe repatriation and resettlement of refugees and IDPs, and actively defend civic space and political freedoms. Elections that fail to meet regional and international standards should not be endorsed.

Elections Must Crown the Transition—Not Bury It

South Sudan’s crisis is not the absence of elections, but the absence of accountable governance and political will. Elections held without a constitution, judicial reform, security sector reform, credible population data, and the safe return of displaced citizens are not democratic milestones—they are destabilizing shortcuts.

Under the R-ARCSS and international democratic norms, legitimacy flows from compliance, not convenience. For peace to endure and democracy to take root, the transition must be completed before ballots are cast. Anything less risks returning South Sudan to conflict—this time under the cover of elections.

The writer, Kenyi Ya Kenyi, is a South Sudanese human rights lawyer. He can be reached via email at kenyiyasin@gmail.com.

The views expressed in ‘opinion’ articles published by Radio Tamazuj are solely those of the writer. The veracity of any claims made is the responsibility of the author, not Radio Tamazuj.