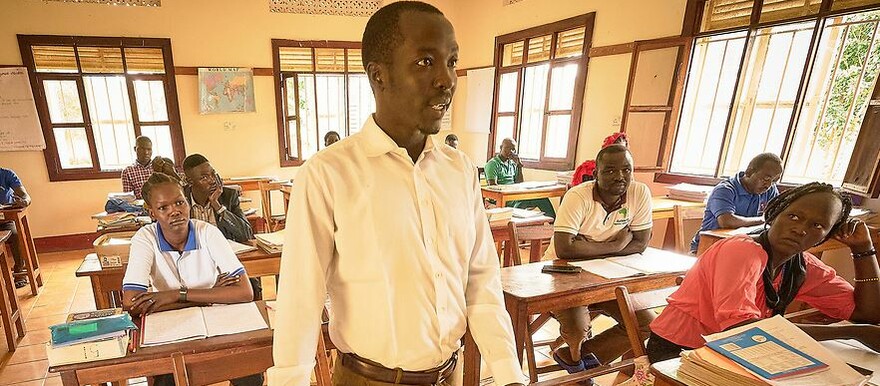

During a recent visit to a government-owned primary school in Juba, a group of tutors from Windle Trust International were very impressed with the joyous welcome by the head teacher. The tutors, hired to train teachers in literacy and numeracy, were on a joint tour to familiarize themselves with the locations of primary schools to which they were deployed.

“I thank Windle Trust very much,” Fatima Lino Yobo, head teacher of El Giada Girls Primary School said, as the tutors took seats, getting ready to talk to her about their mission.

“This English I am using to talk to you, I got it from Windle Trust here in Juba,” she said with a touch of pride, prompting a prolonged joyous handclapping from the tutors who were impressed with her command of the English language.

She is among a few hundred South Sudanese with an Arabic language background who luckily benefitted from a nationwide Intensive English Course (IEC) that Windle Trust used to implement in partnership with the Government of South Sudan during the “good old days.” However, following the armed conflict in 2013 and 2016 across the country, the IEC soon became one of the least priorities for Western donors; much attention was put on funding lifesaving activities like healthcare, provision of potable drinking water, shelter, food security, and livelihoods, to cite but a few areas of concern.

Earlier Flora Santo, the head teacher of Atlabara West Primary School, had expressed disappointment over the apparent suspension of English language training across the country. According to her, many teachers of Arabic language background who have not benefitted from the IEC were quitting teaching to engage in different businesses that do not require any English language proficiency. She advised that Windle Trust International consider resuming the IEC to benefit Arabic language speakers so they can easily access employment opportunities.

Listening to the two head teachers brings to mind fond memories of hundreds of South Sudanese of all professional backgrounds and walks of life who benefitted from the IEC that Windle Trust International used to implement in partnership with the Government of South Sudan through the National Ministry of General Education and Instruction (MOGEI); teachers, customs staff, lawyers, to mention but a few. Many beneficiaries of this program are now working either in the public or private sectors, including in the humanitarian and development nongovernmental organizations.

So, how can the bulk of South Sudanese citizens of Arabic language background be helped to access English tuition so that they can compete favorably well in search of limited employment opportunities or in running their business that may require some background in English? Remember, there has been a recent wave of South Sudanese fleeing the war in neighboring Sudan… If not provided with intensive courses in the English language, such people might find it hard to cope with life as they may not easily acquire meaningful jobs regardless of their academic qualifications!

According to the Constitution of the Republic of South Sudan (2011), English shall be the official working language in the Republic of South Sudan, as well as the language of instruction at all levels of education (Pg. 3). This implies that one’s command in English becomes an important requirement in accessing employment either in the public or private sectors.

According to many research findings, English is generally held in high esteem as the language of modernity, parliamentary democracy, technological progress, and national unity whose acquisition guarantees the beneficiary (user) unlimited vertical social mobility. Such a view seems to link well with the ethnic composition of South Sudan as a “multi-ethnic, multi-cultural, multi-lingual, multi-religious and multi-racial” state (Constitution of the Republic of South Sudan, 2011). The choice of this language as an official medium of communication, therefore, must serve as a “unifying” factor for the heterogeneous communities of South Sudan.

South Sudanese leaders probably thought wisely of having made English the official language of communication and medium of instruction in all the academic institutions across the country. However, much support towards a larger population of citizens who studied in Arabic language is required. It is pitiful to watch them being “victims” of their government’s language policy change. During their time, Arabic was the official language and medium of instruction. Many have studied and become professionals in different fields yet find themselves unable to function in English!

With the relative peace prevailing across South Sudan, it is incumbent upon the government to attract donors who would be able to fund the provision of Intensive English Courses (IEC) to South Sudanese of Arabic language background. Humanitarian and development agencies such as Windle Trust International could be contracted to run the IEC across South Sudan to benefit as many citizens from various professional backgrounds as possible.

Such an intervention could lead to the promotion of peace across the country as youth can compete equally amongst themselves for employment opportunities. More often than not, youth in many regions of South Sudan have cried foul about employment in the NGO sector being dominated by citizens from particular states, counties, or even ethnic groups. They have often expressed their resentment by issuing letters threatening expulsion of South Sudanese citizens from particular regions deemed to have “grabbed our jobs.” It is easy and within the means of the government to reverse such situations by availing equal opportunities to its citizens to acquire English, now the official language and medium of instruction in all educational institutions across South Sudan since the country gained independence in 2011 – immediately after the conduct of a popular referendum on secession of Southern Sudan from Sudan in 2009.

Since South Sudanese are much more inclined to East Africa now, the acquisition of English language proficiency could greatly ease travel within and across member states such as Uganda, Kenya, Tanzania, or even Rwanda. It should be noted that many South Sudanese families now send their children to study in schools and universities within these countries – with Uganda seemingly being a preferred destination, probably on account of its proximity or ease with which people get along in life with the citizens there.

English language proficiency becomes crucially helpful in such a context where the South Sudanese parent, sibling, relative, or maid might have to interact with school authorities about their children’s academic performance or character. More important is also the need for such people to be able to interact with immigration officials with ease whenever they are entering or exiting a particular Anglophone country within the region. The acquisition of this much-touted language could also give the South Sudanese living in those countries the much-needed knowledge and skills to interact with health professionals over the health or medical conditions of their children, and generally, the ease to move about. To speak a second language, according to polyglots, “is to have a second soul.” What this means is that languages are the key to a better understanding of cultures. A language helps to shape our ideas, and learning another language provides us with a wider vision of the world.

All in all, it is crucially advantageous for the government to help thousands of South Sudanese of Arabic language background acquire English through the provision of IEC across the country. In so doing, the government would be playing a great role in ensuring that its public servants have a “uniform” language in their official communication, unlike the current situation where some of them continue to handle official matters in Arabic and others in English. It is, certainly, not an easy feat, but the government should work hard to attract development partners to help it implement IEC across South Sudan.

Alfred Geri is an experienced communicator and educationalist who has a passion for the provision of IEC. He can be reached via algeri2003@yahoo.com.

The views expressed in ‘opinion’ articles published by Radio Tamazuj are solely those of the writer. The veracity of any claims made is the responsibility of the author, not Radio Tamazuj.