Our national capital Juba has been experiencing relentless rainfall for several days now. Heavy downpours are, however, not unfamiliar to the people of Juba and the rest of South Sudan.

Over the past five years, the country has received above-normal rainfall. This and the overflowing rivers, have led to severe flooding in various parts, particularly the Upper Nile, Bahr el-Ghazal and Equatoria.

While the intensity of these floods may be unprecedented for many in our generation, instances of severe flooding have precedents. For example, Akobo experienced severe floods in 1917, which prompted the relocation of an Anglo-Egyptian district headquarters, while floods in Bor during the 1960s caused mass displacement.

Recently, the IGAD Climate Prediction and Application Centre (ICPAC), accredited by the World Meteorological Organization, released a report forecasting more than usual rainfall in parts of South Sudan starting August 20

What is unusual, however, is the appearance of blackish rainwater. After heavy intermittent rain on August 21, residents of Juba awoke on Friday to find rainwater looking discolored, raising health concerns. This phenomenon was both unfamiliar and frightening.

Initially, I thought this was an isolated incident, but it became clear that many shared similar experiences. It soon became evident that the issue was widespread in Juba, although only a few had voiced their concerns openly—perhaps waiting for someone to take the lead in ringing the alarm bell.

According to environmental experts, the so-called “black rainwater” is likely attributed to atmospheric pollution, although no confirmatory tests have been conducted yet.

Atmospheric pollution that alters the color of rainwater is mainly caused by particulate matter resulting from human activities such as industrial emissions, vehicle exhaust, and notably, biomass burning, including charcoal production. When organic materials like trees and shrubs are burned, they release a mixture of gases and particulate matter into the atmosphere.

These pollutants can settle on clouds and alter the composition of raindrops when precipitation occurs. The interaction between smoke particles and water vapor can result in darker, discolored rainwater, particularly in areas where deforestation and unsustainable agricultural practices increase the frequency and intensity of burning.

As a journalist with a background in public health, I find this explanation for the polluted clouds and resultant black rainwater highly plausible. In Juba, extensive bush burning releases significant amounts of smoke into the atmosphere, which interacts with clouds and changes the appearance of rainwater. Additionally, clouds can collect pollutants from distant areas as they move.

Another factor that has yet to be thoroughly examined is air traffic. South Sudan’s airspace is frequently used by local flights and those diverted from conflict zones like Sudan. Older aircraft that do not meet modern emission standards may deposit pollutants—such as particulate matter and various nitrogen and carbon oxides—into the atmosphere. These emissions can significantly affect atmospheric conditions and, in turn, the quality of precipitation.

The appearance of blackish rainwater in Juba is a serious concern, with the full extent of its damage remaining largely unclear and potentially taking a long time to assess. An urgent intervention is needed. However, it seems our fears may be justified as this situation risks becoming the “new normal”.

Since the civil war began in 2013, our economy has suffered severely, heading towards a collapse, with inflation now well over 200,000 per cent. Civil servants have gone unpaid for over a year, and the promise of better conditions in 2025—with salaries expected by the 24th of each month—has yet to materialize. For many, engaging in the charcoal business has become the only viable option, despite the negative implications.

Some may dismiss the scientifically proven fact that large-scale deforestation harms both our health and the environment, citing that charcoal production is a tradition passed down through generations. While this reasoning has some validity, one thing is unprecedented: we are clearing vast areas to make charcoal, which is sold locally and internationally to cover basic expenses such as food, school fees, and medical costs. Thus, a holistic socio-economic approach is needed to tackle this phenomenon, along with an urgent awareness regarding sustainable environmental practices and public health.

We must thank the National Ministry of Environment for its advocacy during the dredging saga, promoting the conservation of our natural resources and biodiversity. The experience of encountering blackish rainwater serves as a warning and a wake-up call that requires similar attention from other governmental and non-governmental agencies.

Let us remember the minor prophet Hosea of the biblical era, who lamented his people’s failure to embrace knowledge and teach God’s ways, leading ultimately to disaster (Hosea 4:6: “My people are destroyed for lack of knowledge…”). We must not become like the Israelites of Hosea’s time, living in ignorance while watching our fears unfold before us.

Research indicates that pollutants in the atmosphere not only degrade rainwater quality but also pose severe health risks to local populations as these contaminants enter our ecosystems and water sources. The World Health Organization (WHO) recognizes atmospheric pollution as a major public health emergency, responsible for approximately 7 million premature deaths globally each year.

Exposure to air pollution can particularly affect pregnant women, increasing the risk of hypertensive disorders that may lead to premature births and low birth weights. Indirectly, human health is further compromised as contaminated rainwater seeps into soil and aquatic ecosystems, impacting both terrestrial and aquatic life. As we depend on soil and water for our sustenance, the resulting health impacts are inevitable.

In Juba, rain is traditionally viewed as a relief, providing water for household chores, especially now that water tankers sell a barrel for up to SSP10,000. However, this toxic-looking rainwater undermines that relief. Safe and readily available water is a fundamental human right essential for public health.

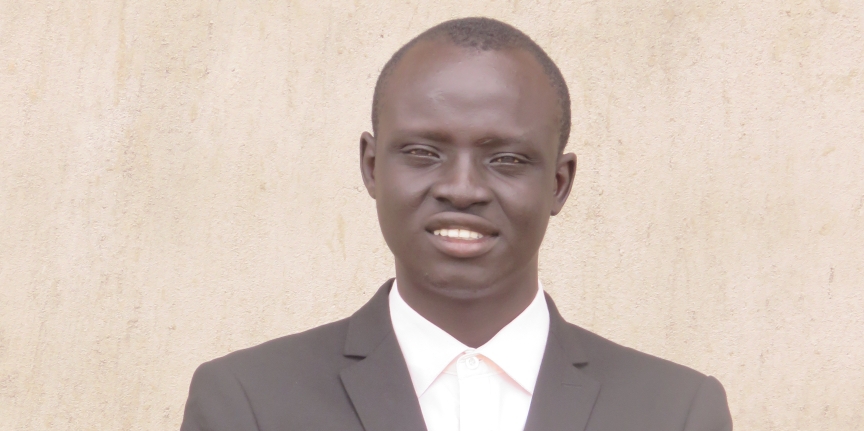

The writer, Manas James Okony, is a South Sudanese journalist and an author. He can be reached via email: manasjokony@gmail.com.