Children arriving at Renk’s transit centre in South Sudan’s Upper Nile State are part of a growing wave of displacement triggered by the war in neighbouring Sudan, which erupted in April 2023.

As fighting spread across towns and cities, homes were destroyed, schools closed, and basic services collapsed. Families fled with little warning, travelling on foot or in overcrowded vehicles, often unsure of their destination. Many crossed into South Sudan, seeking relative safety.

By the time they reach Renk, children are exhausted, traumatised and uncertain about what comes next. Some arrive separated from parents or caregivers, while others have spent days or weeks moving through insecure areas to escape the violence.

Inside the transit centre, one space stands out.

A simple structure, a safe space

The child-friendly space is housed in a modest iron-sheet building, painted blue, just off the main transit area. Outside, a large playground stretches wide enough for groups of boys to run freely and play football – a rare sight in a place defined by waiting.

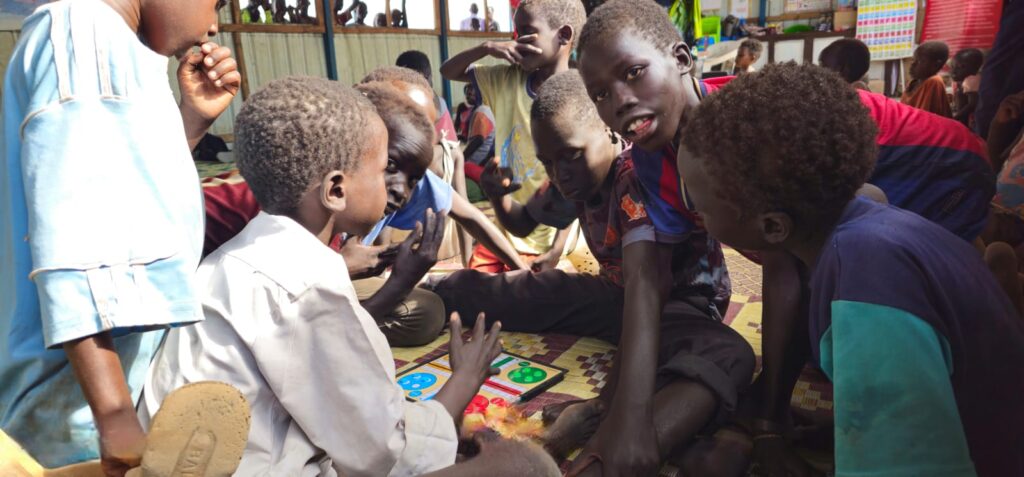

Inside, the atmosphere changes. Walls are covered with children’s drawings – brightly coloured sketches of houses, rivers, animals and people. One depicts a Save the Children vehicle, another a smiling caregiver. Bright mats line the floor, and simple toys are arranged along the edges. Laughter, singing and the scratch of crayons on paper cut through the constant noise of the centre.

For a few hours each day, the space offers children something rare: safety, routine, and the chance to be children again.

“These children arrive in shock,” says Nyagua Taban, a mental health and psychosocial support officer with Save the Children. “Some cannot communicate or interact with others when they first come. This space helps them slowly open up.”

Seventeen-year-old Sandy Steven fled Sudan earlier this year after fighting intensified near her home.

“The road was not safe,” she says. “We would move, then stop because of the fighting. Sometimes we didn’t know where the bullets were coming from. By the will of God, we reached here.”

Her journey to South Sudan took five days. Along the way, she saw families sleeping outdoors and children going without food. When she arrived in Renk, no shelter was ready, and her family slept outside the transit centre before receiving assistance.

“You leave school, you leave your friends, and suddenly you are in another country,” she says. “When you sit at home, you think a lot.”

Healing through play and art

The child-friendly space helps children cope with the psychological impact of displacement. Through singing, dancing, storytelling and drawing, staff encourage children to express emotions they cannot put into words.

“You find a child who cannot tell you what they are going through,” Nyagua explains. “But when they draw, you can see it. Arts help release trauma.”

Activities are tailored to younger children’s emotional and cognitive development. “Many children lack family attachment when they arrive,” Nyagua says. “But here, they make friends. They feel secure. Some do not want to leave at the end of the day.”

A temporary classroom

With no formal school operating inside the transit centre, the space also serves as a temporary classroom. Staff teach letters, numbers and basic English skills many children lost when schools closed during the conflict.

Ten-year-old Jima Acheil says the centre gives her something to look forward to. “I come to play Ludo, cards, football and cars,” she says. “And I come to study. Whenever I come here, I am happy.”

Nearby, eight-year-old Sebit Jim runs onto the football field outside. “I like playing football, cards and ludo,” he says. “Thank you, Save the Children. Now I can play games.”

Fourteen-year-old Ghail Mohamed Abdullah fled Sudan with her mother after their neighbourhood became unsafe. Inside the centre, she carefully colours pictures of rivers, birds and homes – scenes from a life interrupted.

“I learned English here,” she says, listing words she now knows: “Mother, father, window, chair.” She adds: “1, 2, 3…10. I didn’t know how to count in English before.” Staff say such progress is vital for children whose education was abruptly disrupted by war.

Rising needs, limited resources

Arrivals from Sudan continue each week, increasing pressure on Renk’s facilities. Community facilitator Layla Ajdan says the child-friendly space is already stretched.

“When children arrive from Sudan, they come with many problems,” she says. “But when they come here and play or study, they begin to change.”

She adds that staffing and materials are limited. “We are only two workers here. If we had more materials – boards, music tools – more children would benefit.”

Nyagua warns that funding constraints limit expansion, particularly in Abu Khadra settlement, where many families are being relocated. “These children are still affected by the war,” she says. “They still need support.”

In a transit centre shaped by uncertainty and loss, the blue iron-sheet building and its wide playground offer a fragile sense of normalcy. For children who crossed the border to escape war, it is a place where laughter returns – and where healing slowly begins.