Several members of South Sudan’s parliamentary finance committee confirmed that the central bank disclosed plans to print more money as a short-term measure to address a severe liquidity crisis—contradicting the bank’s public denial earlier today.

The central bank had dismissed an Eye Radio report that it planned to print more currency to ease cash shortages affecting government salary payments, calling the story “false and misleading.”

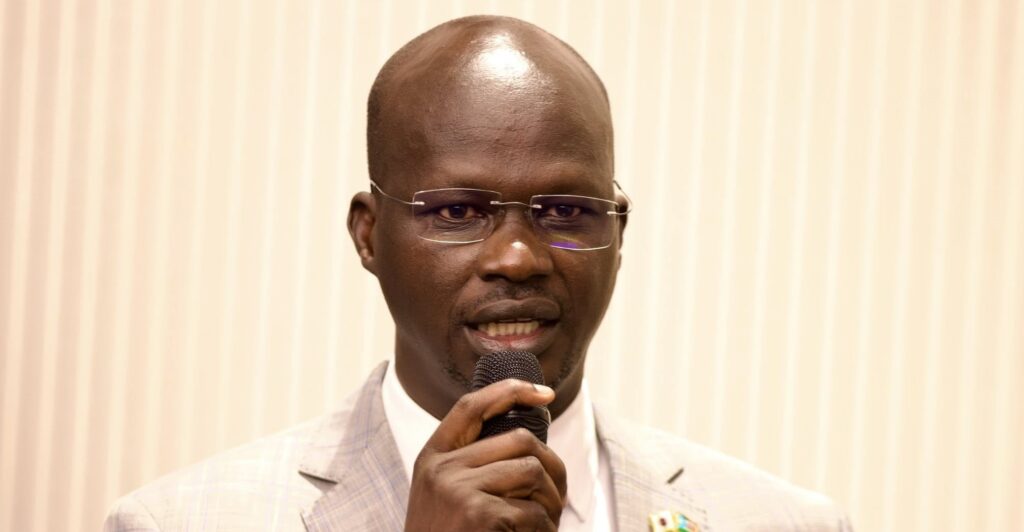

However, lawmakers who summoned Central Bank Governor Dr. Addis Ababa Othow this week told Radio Tamazuj on Wednesday that he revealed in a closed-door meeting that printing more money was being considered as an urgent solution.

Gatkuoth Wat Joar, a finance committee member, said that the bank governor acknowledged the liquidity shortage and outlined the plan. “We asked the governor about the cash crisis. He said there is no liquidity in the bank but that they have a short-term plan: printing more money to meet market demand and pay civil servants,” Wat said.

He added that the governor’s statement was recorded and witnessed by the South Sudan Broadcasting Corporation (SSBC). “They are just denying. The bank governor clearly said they plan to print money—this was in the meeting, and I was there,” Wat insisted.

Though the central bank’s public statement on Wednesday denied any plans to print money, it acknowledged an “urgent plan” to address liquidity demands.

Bank Governor Addis Ababa was quoted in parliament as saying, “In the short term, we have made it clear that there is an urgent need to print money to meet the high demand for liquidity. But in the medium and long term, we are looking at how to address currency management.”

The reversal follows public concerns over potential hyperinflation.

Economists warn that increasing the money supply without economic growth could devalue the South Sudanese pound (SSP) and worsen inflation.

Policy analyst Baboya James said past money-printing efforts—such as those between 2011 and 2016—led to currency collapse, rendering smaller denominations worthless. “Printing more will weaken the SSP further. People hoard cash instead of circulating it, so injecting money won’t solve the problem,” he said.

James warned that without structural reforms, the move could trigger runaway inflation. “If the government prints 1,000 or 5,000 SSP notes, soon even buying tomatoes will require absurd amounts. We must address why money isn’t circulating formally instead of just printing more.”

Dr. Akim Ajieth Buny, an economics lecturer at Dr. John Garang Memorial University, told Radio Tamazuj that printing more money would further weaken the South Sudanese pound (SSP) and fuel inflation.

“Printing more money has never worked as an economic solution—it won’t work here,” Buny said. “Flooding the market with cash will only devalue the pound further. Soon, $100 could exchange for over a million SSP.”

Buny urged the government to declare bankruptcy, arguing it would unlock international bailouts. “Admitting failure—that salaries can’t be paid or the currency is collapsing—would allow the IMF and World Bank to intervene,” he said.

However, he acknowledged such a move could require leadership changes. “The IMF may demand resignations, including the finance minister or central bank governor,” he said, citing Greece and Cyprus’ post-2009 recoveries after similar measures.

Buny suggested introducing a new currency to curb hoarding, alongside withdrawal limits of 1,000–5,000 SSP daily to stabilize banks. He also recommended pegging the SSP to the U.S. dollar, though he noted this requires substantial reserves.

“Saudi Arabia fixed its riyal at 3.75 per dollar in 1986, but it had strong reserves,” he said. “South Sudan must build reserves through transparent oil revenue management first.”

However, Prof. Abraham Matoch Dhal, former vice-chancellor of Dr. John Garang University, defended the move as routine central bank practice. “If the budget requires more money in circulation, printing is normal. The issue is ensuring it aligns with economic needs,” he said.

Dhal argued that South Sudan’s budget expansion necessitated additional currency. “When budgets grow from billions to trillions, money supply must follow. The real failure was not printing enough earlier to match fiscal demands,” he added.

Civil society activist Ter Manyang Gatwech warned that previous money-printing failed to stabilize salaries or prices. “The central bank, finance ministry, and parliament must collaborate on sustainable policies. South Sudan lacks even basic coins—this reflects deeper mismanagement,” he said.

Manyang urged authorities to tackle corruption and hoarding. “Printing money alone won’t help if officials stash cash in homes. We need transparency and incentives to bring money into banks.”

Last month, South Sudan’s finance minister Dr. Marial Dongrin Ater acknowledged persistent cash shortages. The oil-dependent economy remains vulnerable to external shocks, with limited progress on diversification.