In South Sudan, it is known that from April to June each year, the farmers would be busy trying to make preparations before the beginning of farming activities. However, it appears that this rainy season’s rain is arriving later than in prior wet seasons. This article attempts to highlight the more realistic agricultural potential in South Sudan, focusing on opportunities in this crucial sector and providing a concise analysis of its effects on households and overall economic conditions. It is based on my own lessons learned in the field of farming. Like many of my trained professional peers, I think each country’s economy has its own internal constraints and features governed by the real economy.

Based on my experience partaking in agricultural practices, the majority of people in South Sudan, agriculture is the primary source of income, with more than 90% of the land in South Sudan being arable. Additionally, it possesses untapped land-based fisheries, cattle, as well as the Nile and subterranean water resources. Furthermore, with 80% of the population living in rural areas and relying primarily on subsistence farming, South Sudan is one of Africa’s most productive countries, contributing 35% of the country’s non-oil GDP (FAO, 2015). Only 5% of South Sudan’s 30 million hectares of arable land is utilized – actually under cultivation, despite the ideal soil conditions, favourable climate, and a lot of water. Crop yields are incredibly poor, which has a negative impact on the majority of South Sudanese’s earnings and their standard of living.

In the interest of the farmers and the economy, South Sudan needs to create a viable agriculture sector that serves as the main source of food security for the nation and contributes to the export market for true economic diversification, which is ultimately crucial for our microeconomic development and long-awaited growth targets. The sector output is poor because crop production is reduced, distribution systems and markets are disrupted, and most households have had limited access to a variety of food types as a result of a lack of agricultural input, including issues with financing, banking credit, seeds, fuel, machines and equipment, fertilizers, poor advisory services, and ineffective irrigation management. At the moment, South Sudan is largely reliant on the importation of all agricultural inputs, which are transported across tough terrain and treacherous roads, as in the case of the Northern Upper Nile.

Apart from the defunct agricultural projects in Nzara in Western Equatoria, Aweil Rice in Northern Bahr-El-Ghazal, and government-owned mechanized agricultural schemes in Renk in Upper Nile, which currently need revitalization programs to reinforce agricultural production positively, there hasn’t been much government investment in this sector. South Sudan’s agricultural productivity growth depends critically on investment in new infrastructure and technologies in both the rain-fed and irrigated agricultural sub-sectors, yet this is not a priority it deserves from concerned government agencies. Prioritizing the agriculture sector would encourage inclusive economic growth in rural areas by encouraging employment for most women and young people, increasing income and investment, and ultimately assisting in raising the living standards of those who work in agriculture. By encouraging agricultural growth through sustainable agricultural policies, it will be possible to encourage the economic growth of many farmers to grow a variety of crops for the purpose of food security as well as cash crop exports and international trade to support the external value of our local currency.

When I appeared on SSBC promoting my agricultural project in Renk, Northern Upper Nile, sometime in the year 2020, a friend of mine who was sceptical of my decision to pursue a farming career didn’t believe it. He expressed mixed emotions about seeing me and felt as though I had degraded myself. My friend believes in a big illusion that holding public office is a source of pride and would be too much for me. “Stephen, this farm is your deserved place,” he added. We may discuss this fictitious civilization of idleness and redundant work with him. But in reality, our inability to expand agricultural productivity has been a significant factor in our current widespread poverty. Most of sub-Saharan Africa’s agricultural production has been boosted through investments in basic public facilities, improvements to institutions and laws over the past few decades, while South Sudan has lagged behind.

Since 2005, the South Sudanese government has undertaken a number of attempts to revive the agricultural industry. Farmers have received agricultural tractors and equipment, and the sector has received public funding, but these projects lack coherence and durability. The most recent occurred in 2015 when President Salva Kiir Mayardit issued an order to distribute 1,000 tractors. This audacious action would have brought the self-reliance strategy to life. If this significant investment had been used properly, the agriculture plan would have been operationalized and realized. The renowned cartoonist Adjija Achuil depicted “a country with one tractor and one thousand V8 vehicles” in one of his publications, referencing the agricultural state of South Sudan. Without agriculture’s contribution to the economy, people will be blaming unidentified factors for recessions and financial crises, which are always accompanied by higher unemployment rates, inflation, currency depreciation, and other symptoms of hardship. They will also be impatient for political measures like austerity that are meant to hasten the economy’s recovery and general well-being.

South Sudan’s Vision 2040 and the R-NDS, the country’s revised national development strategy. The R-NDS strives to maintain economic stability, reduce adverse effects on the human condition, and advance sustainable development. In order to ensure food security for the country’s expanding population, generate income and jobs for its rural residents, and preserve the environment, the South Sudanese government is to embark on the expansion of the agriculture, forestry, livestock, and fisheries subsectors in accordance with the adopted policies. In light of this, it is essential to ensure that policy priorities in the current context take into account societal needs and socio-economic conditions in order to encourage agricultural expansion through sustainable agricultural transformation, which may stimulate economic growth for many people, regardless of whether they depend on agriculture. Agriculture is crucial in fostering trust in economic factors, including employment, earnings, price, and interest rate, that have a significant impact on the demand and supply for consumer goods.

In my opinion, and to sum up, it appears that our shortcoming is that we have high expectations for things that have already been made by others and have a highly showing off style, even though we haven’t done much to create them. The development of South Sudan’s agriculture sector is hampered by a single enemy: the culture of dependency. Let us hope we have learned enough to continue our development efforts for food independence with assurance. Under the guidance and control of the national ministries of finance, agriculture, livestock and fisheries, and the Bank of South Sudan, commercial banks and the Agricultural Bank of South Sudan must now be given the mission and instructions to implement agricultural policy and provide strong management standards and financial resources. This strategy would be dependent on a wider variety of interconnected duties carried out by these important institutions, and in addition, it is essential for South Sudan to operationalize the identified programs as indicated below, including but not limited to:

1) The creation of research facilities and institutes dedicated to agriculture across the nation.

2) Stabilizing the South Sudan Agricultural Bank and commercial banks to give finance for agriculture a top priority.

3) Having timely access to agricultural supplies prior to the rainy season.

4) Offering banking credit and financial services to women, young people, and small-scale farmers.

5) Reviving the defunct agricultural schemes in Aliap, Nzara, Aweil, and Renk.

6) Improving water management and irrigation systems.

7) The development of rural agricultural markets internally and externally.

8) Building an updated crop storage system in the production centres.

9) Providing transportation services connecting consumer and producer centres.

10) Giving agricultural and livestock inputs extension services.

11) Farmer empowerment and training.

12) Empowerment of the women

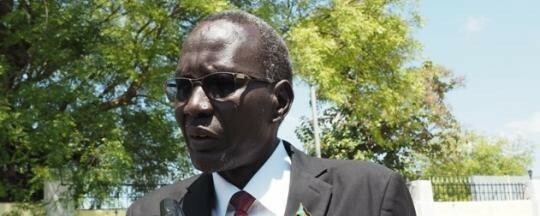

The author, Mr Stephen Dhieu Dau, is a former South Sudanese minister & farm – holder in Upper Nile State.

The views expressed in ‘opinion’ articles published by Radio Tamazuj are solely those of the writer. The veracity of any claims made is the responsibility of the author, not Radio Tamazuj.